Sailboat Hardware

Sailboat Parts Explained: Illustrated Guide (with Diagrams)

When you first get into sailing, there are a lot of sailboat parts to learn. Scouting for a good guide to all the parts, I couldn't find any, so I wrote one myself.

Below, I'll go over each different sailboat part. And I mean each and every one of them. I'll walk you through them one by one, and explain each part's function. I've also made sure to add good illustrations and clear diagrams.

This article is a great reference for beginners and experienced sailors alike. It's a great starting point, but also a great reference manual. Let's kick off with a quick general overview of the different sailboat parts.

General Overview

The different segments

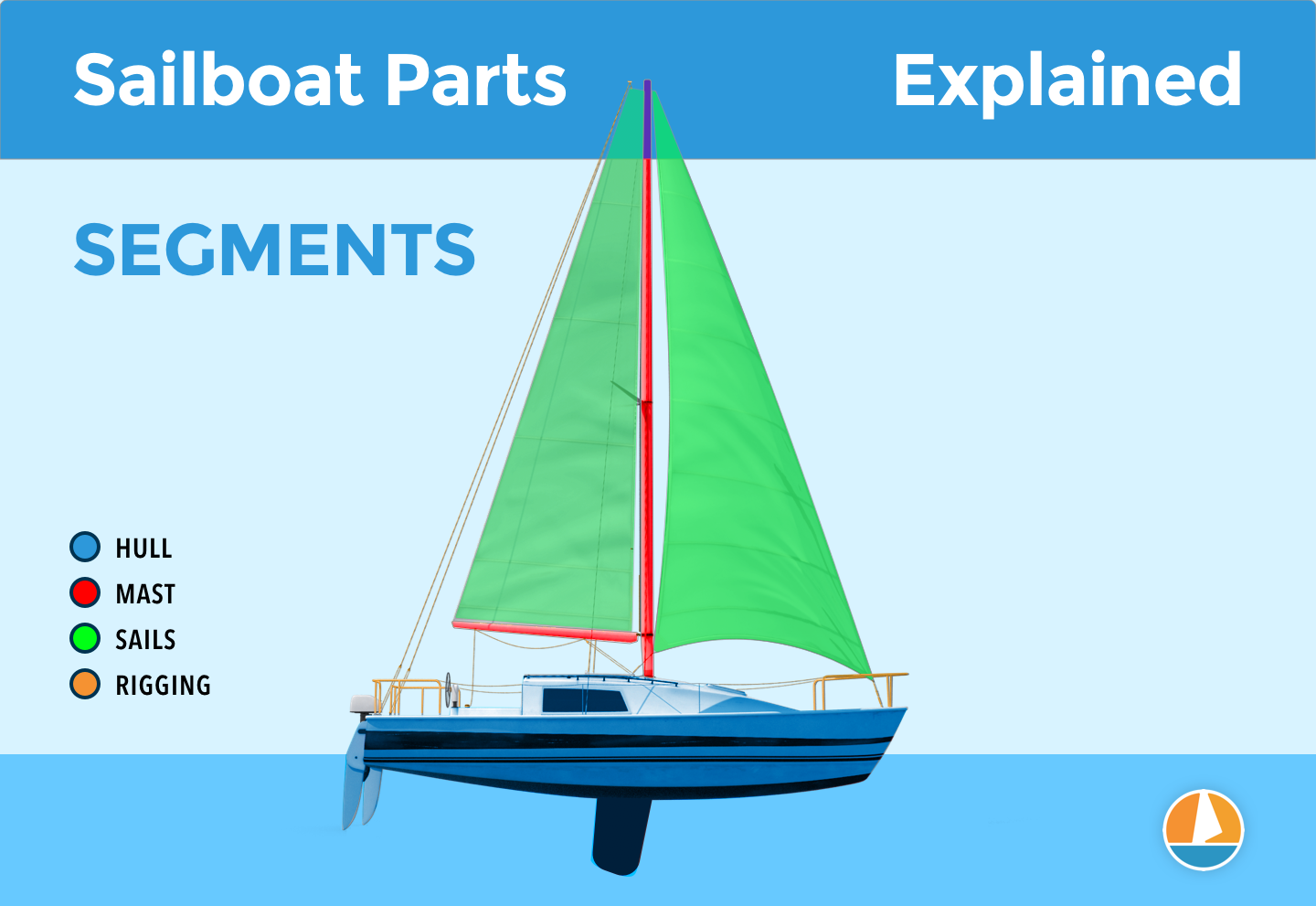

You can divide up a sailboat in four general segments. These segments are arbitrary (I made them up) but it will help us to understand the parts more quickly. Some are super straightforward and some have a bit more ninja names.

Something like that. You can see the different segments highlighted in this diagram below:

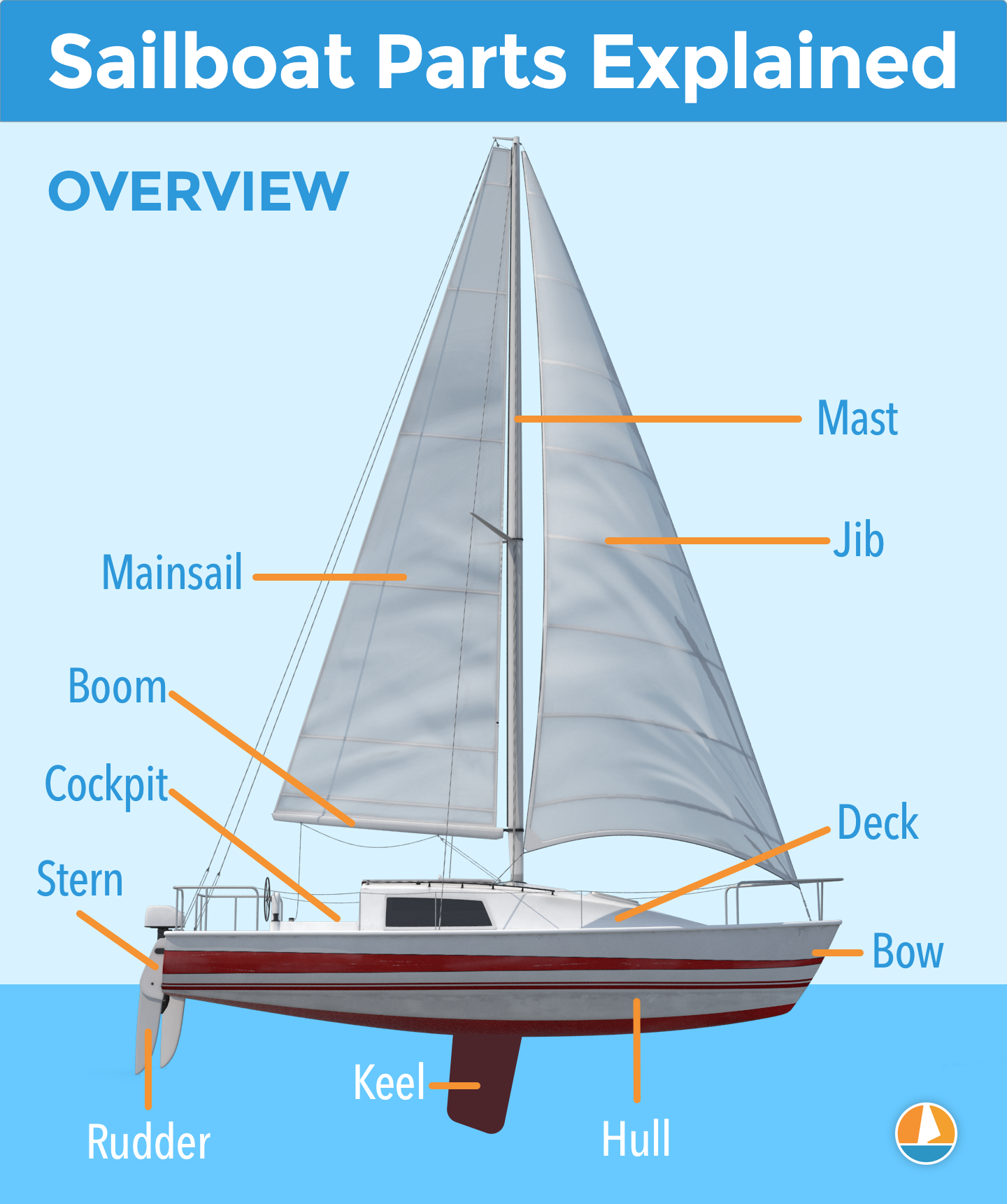

The hull is what most people would consider 'the boat'. It's the part that provides buoyancy and carries everything else: sails, masts, rigging, and so on. Without the hull, there would be no boat. The hull can be divided into different parts: deck, keel, cabin, waterline, bilge, bow, stern, rudder, and many more.

I'll show you those specific parts later on. First, let's move on to the mast.

Sailboats Explained

The mast is the long, standing pole holding the sails. It is typically placed just off-center of a sailboat (a little bit to the front) and gives the sailboat its characteristic shape. The mast is crucial for any sailboat: without a mast, any sailboat would become just a regular boat.

I think this segment speaks mostly for itself. Most modern sailboats you see will have two sails up, but they can carry a variety of other specialty sails. And there are all kinds of sail plans out there, which determine the amount and shape of sails that are used.

The Rigging

This is probably the most complex category of all of them.

Rigging is the means with which the sails are attached to the mast. The rigging consists of all kinds of lines, cables, spars, and hardware. It's the segment with the most different parts.

The most important parts

If you learn anything from this article, here are the most important parts of any sailboat. You will find all of these parts in some shape or form on almost any sailboat.

Okay, we now have a good starting point and a good basic understanding of the different sailboat parts. It's time for the good stuff. We're going to dive into each segment in detail.

Below, I'll go over them one by one, pointing out its different parts on a diagram, listing them with a brief explanation, and showing you examples as well.

After reading this article, you'll recognize every single sailboat part and know them by name. And if you forget one, you're free to look it up in this guide.

On this page:

The hull is the heart of the boat. It's what carries everything: the mast, the sails, the rigging, the passengers. The hull is what provides the sailboat with its buoyancy, allowing it to stay afloat.

Sailboats mostly use displacement hulls, which is a shape that displaces water when moving through it. They are generally very round and use buoyancy to support its own weight. These two characteristics make sure it is a smooth ride.

There are different hull shapes that work and handle differently. If you want to learn more about them, here's the Illustrated Guide to Boat Hull Types (with 11 Examples ). But for now, all we need to know is that the hull is the rounded, floating part of any sailboat.

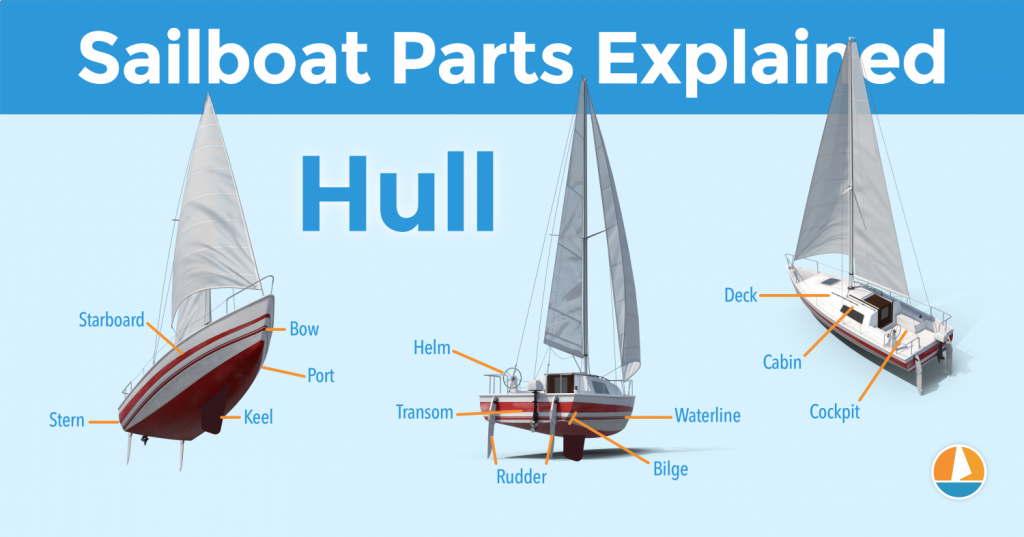

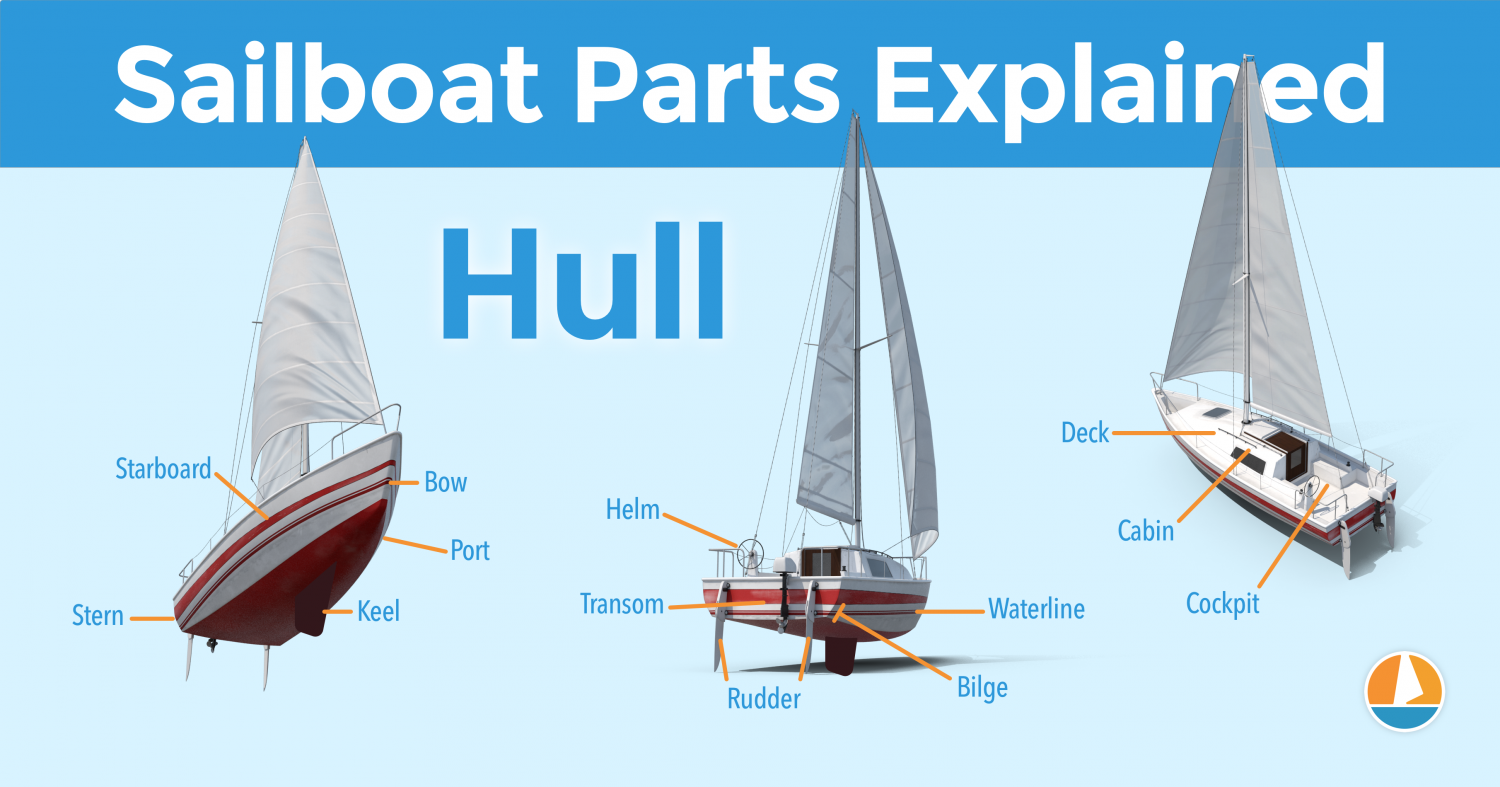

Instead of simply calling the different sides of a hull front, back, left and right , we use different names in sailing. Let's take a look at them.

The bow is the front part of the hull. It's simply the nautical word for 'front'. It's the pointy bit that cuts through the water. The shape of the bow determines partially how the boat handles.

The stern is the back part of the hull. It's simply the nautical word for 'back'. The shape of the stern partially determines the stability and speed of the boat. With motorboats, the stern lies deep inside the water, and the hull is flatter aft. Aft also means back. This allows it to plane, increasing the hull speed. For sailboats, stability is much more important, so the hull is rounded throughout, increasing its buoyancy and hydrodynamic properties.

The transom is the backplate of the boat's hull. It's the most aft (rear) part of the boat.

Port is the left side of a sailboat.

Starboard is the right side of a sailboat

The bilges are the part where the bottom and the sides of the hull meet. On sailboats, these are typically very round, which helps with hydrodynamics. On powerboats, they tend to have an angle.

The waterline is the point where the boat's hull meets the water. Generally, boat owners paint the waterline and use antifouling paint below it, to protect it from marine growth.

The deck is the top part of the boat's hull. In a way, it's the cap of the boat, and it holds the deck hardware and rigging.

Displacement hulls are very round and smooth, which makes them very efficient and comfortable. But it also makes them very easy to capsize: think of a canoe, for example.

The keel is a large fin that offsets the tendency to capsize by providing counterbalance. Typically, the keel carries ballast in the tip, creating a counterweight to the wind's force on the sails.

The rudder is the horizontal plate at the back of the boat that is used to steer by setting a course and maintaining it. It is connected to the helm or tiller.

Tiller or Helm

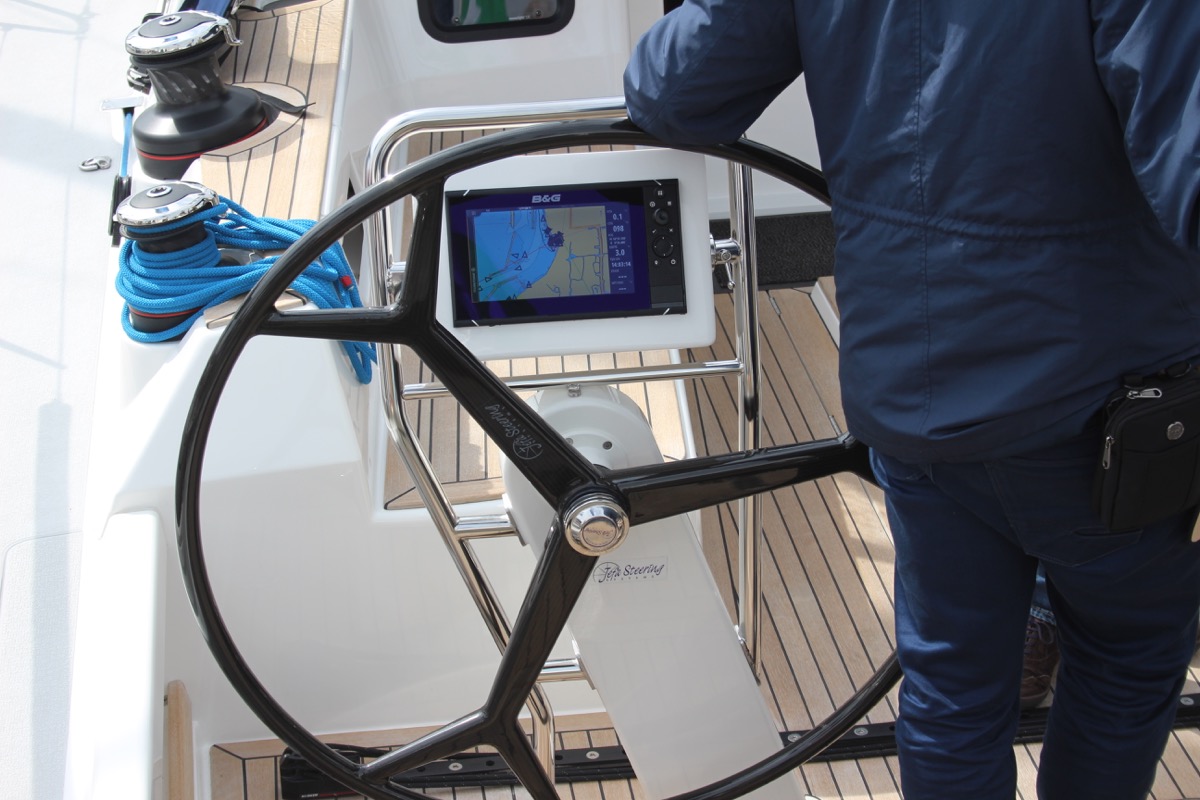

- The helm is simply the nautical term for the wheel.

- The tiller is simply the nautical term for the steering stick.

The tiller or helm is attached to the rudder and is used to steer the boat. Most smaller sailboats (below 30') have a tiller, most larger sailboats use a helm. Large ocean-going vessels tend to have two helms.

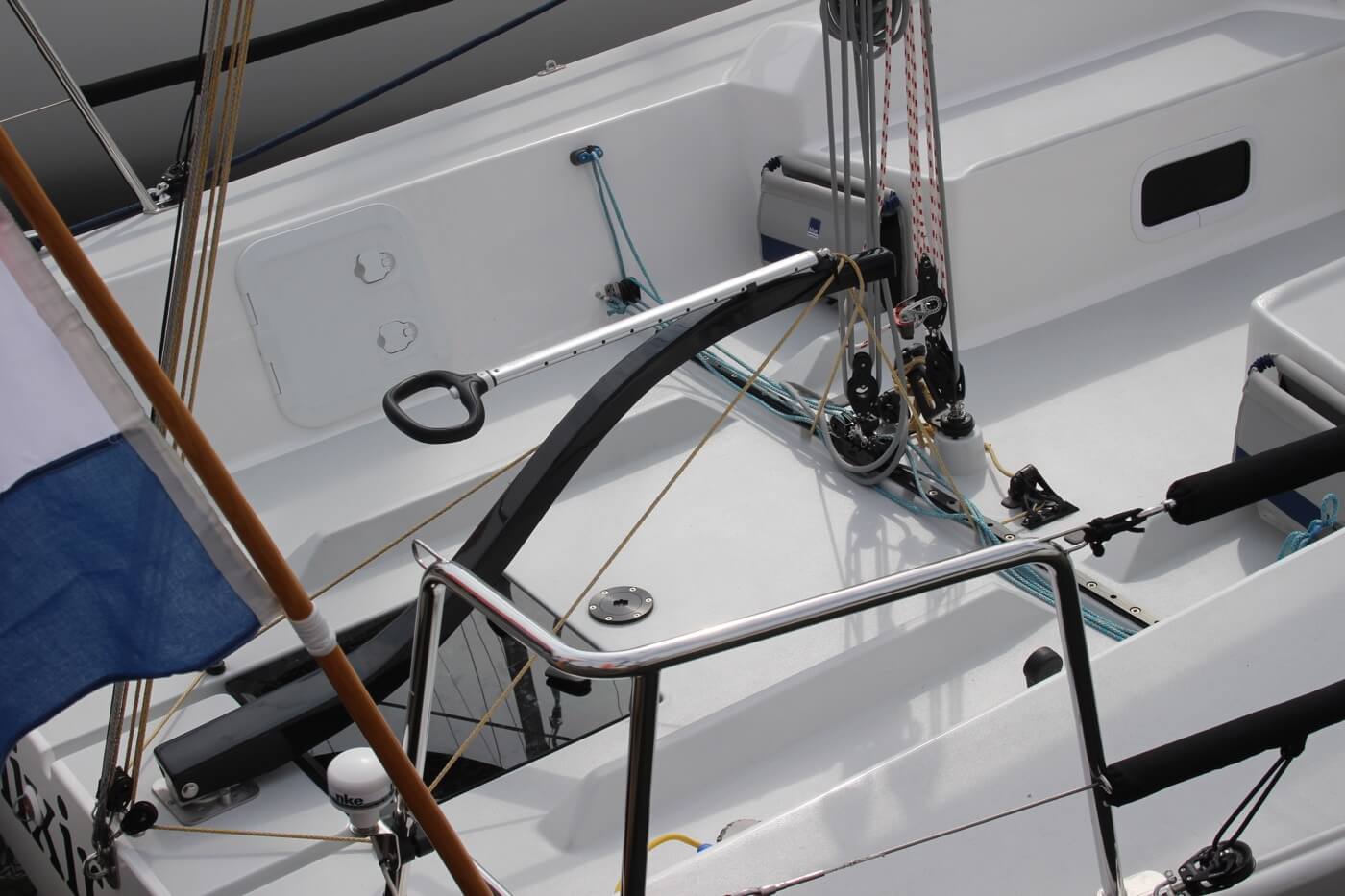

The cockpit is the recessed part in the deck where the helmsman sits or stands. It tends to have some benches. It houses the outside navigation and systems interfaces, like the compass, chartplotter, and so on. It also houses the mainsheet traveler and winches for the jib. Most boats are set up so that the entire vessel can be operated from the cockpit (hence the name). More on those different parts later.

Most larger boats have some sort of roofed part, which is called the cabin. The cabin is used as a shelter, and on cruising sailboats you'll find the galley for cooking, a bed, bath room, and so on.

The mast is the pole on a sailboat that holds the sails. Sailboats can have one or multiple masts, depending on the mast configuration. Most sailboats have only one or two masts. Three masts or more is less common.

The boom is the horizontal pole on the mast, that holds the mainsail in place.

The sails seem simple, but actually consist of many moving parts. The parts I list below work for most modern sailboats - I mean 90% of them. However, there are all sorts of specialty sails that are not included here, to keep things concise.

The mainsail is the largest sail on the largest mast. Most sailboats use a sloop rigging (just one mast with one bermuda mainsail). In that case, the main is easy to recognize. With other rig types, it gets more difficult, since there can be multiple tall masts and large sails.

If you want to take a look at the different sail plans and rig types that are out there, I suggest reading my previous guide on how to recognize any sailboat here (opens in new tab).

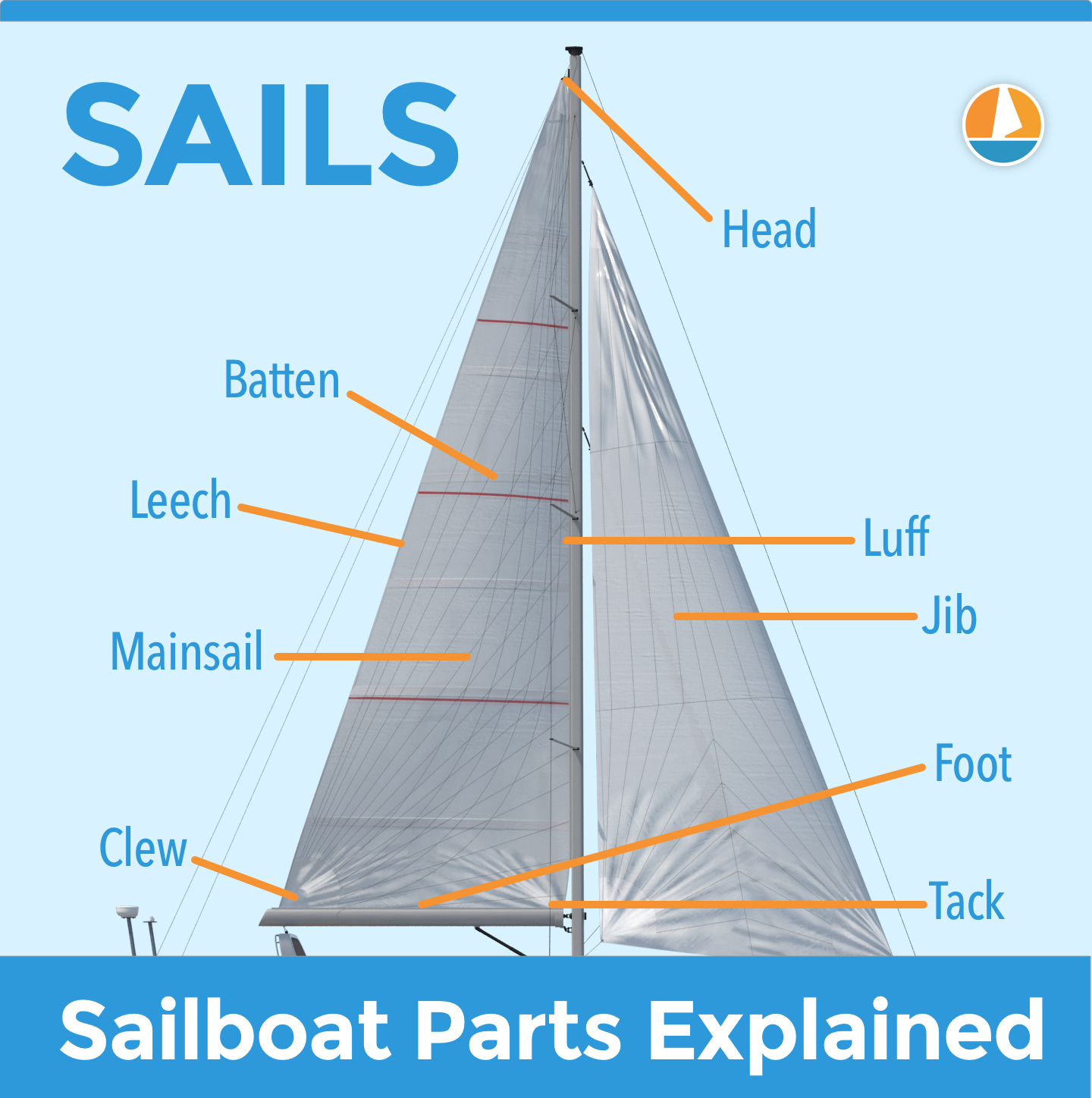

Sail sides:

- Leech - Leech is the name for the back side of the sail, running from the top to the bottom.

- Luff - Luff is the name for the front side of the sail, running from the top to the bottom.

- Foot - Foot is the name for the lower side of the sail, where it meets the boom.

Sail corners:

- Clew - The clew is the lower aft (back) corner of the mainsail, where the leech is connected to the foot. The clew is attached to the boom.

- Tack - The tack is the lower front corner of the mainsail

- Head - The head is the top corner of the mainsail

Battens are horizontal sail reinforcers that flatten and stiffen the sail.

Telltales are small strings that show you whether your sail trim is correct. You'll find telltales on both your jib and mainsail.

The jib is the standard sized headsail on a Bermuda Sloop rig (which is the sail plan most modern sailboats use).

As I mentioned: there are all kinds, types, and shapes of sails. For an overview of the most common sail types, check out my Guide on Sail Types here (with photos).

The rigging is what is used to attach your sails and mast to your boat. Rigging, in other words, mostly consists of all kinds of lines. Lines are just another word for ropes. Come to think of it, sailors really find all kinds of ways to complicate the word rope ...

Two types of rigging

There are two types of rigging: running and standing rigging. The difference between the two is very simple.

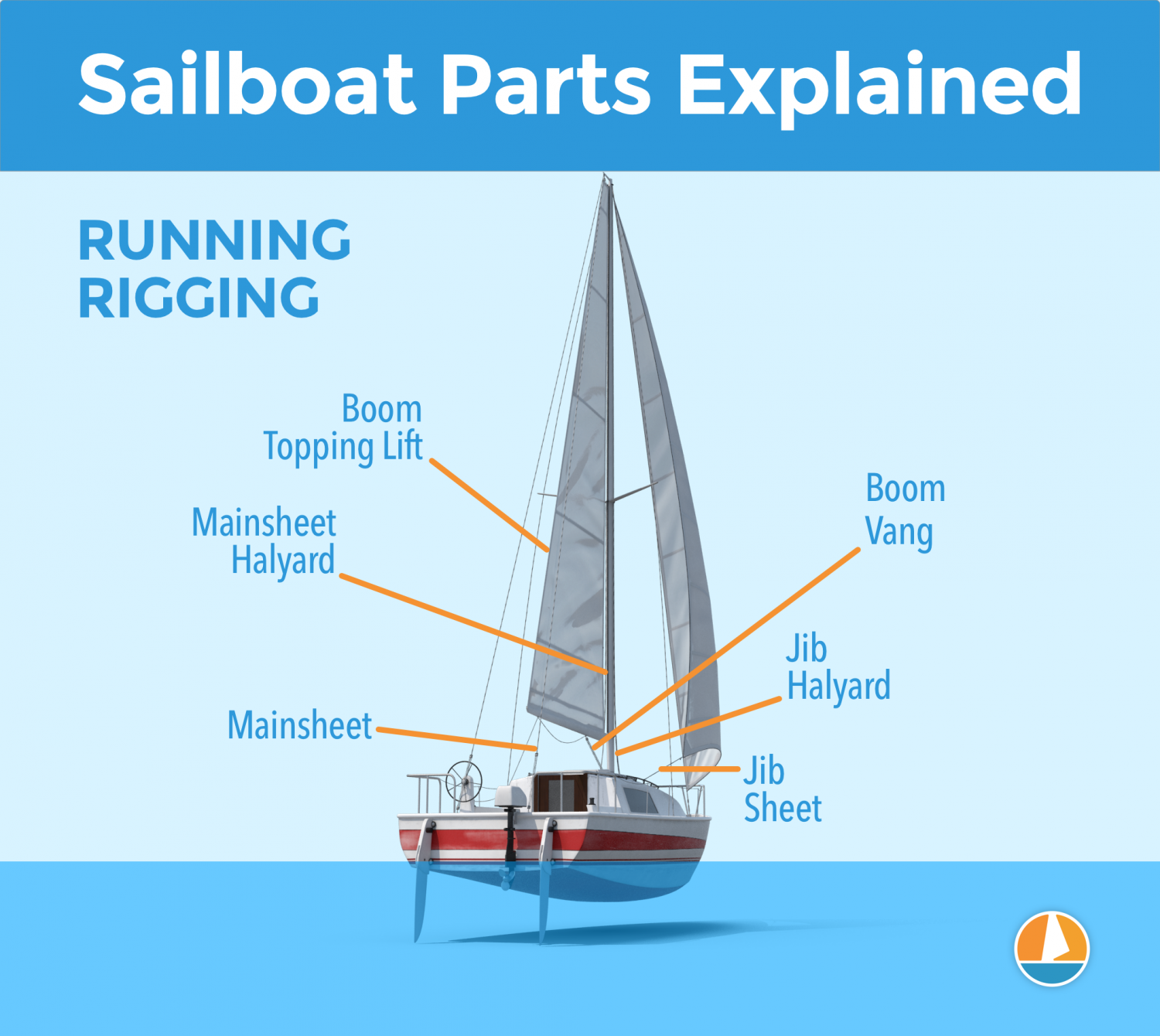

- The running rigging is the rigging on a sailboat that's used to operate the sails. For example, the halyard, which is used to lower and heave the mainsail.

- The standing rigging is the rigging that is used to support the mast and sail plan.

Standing Rigging

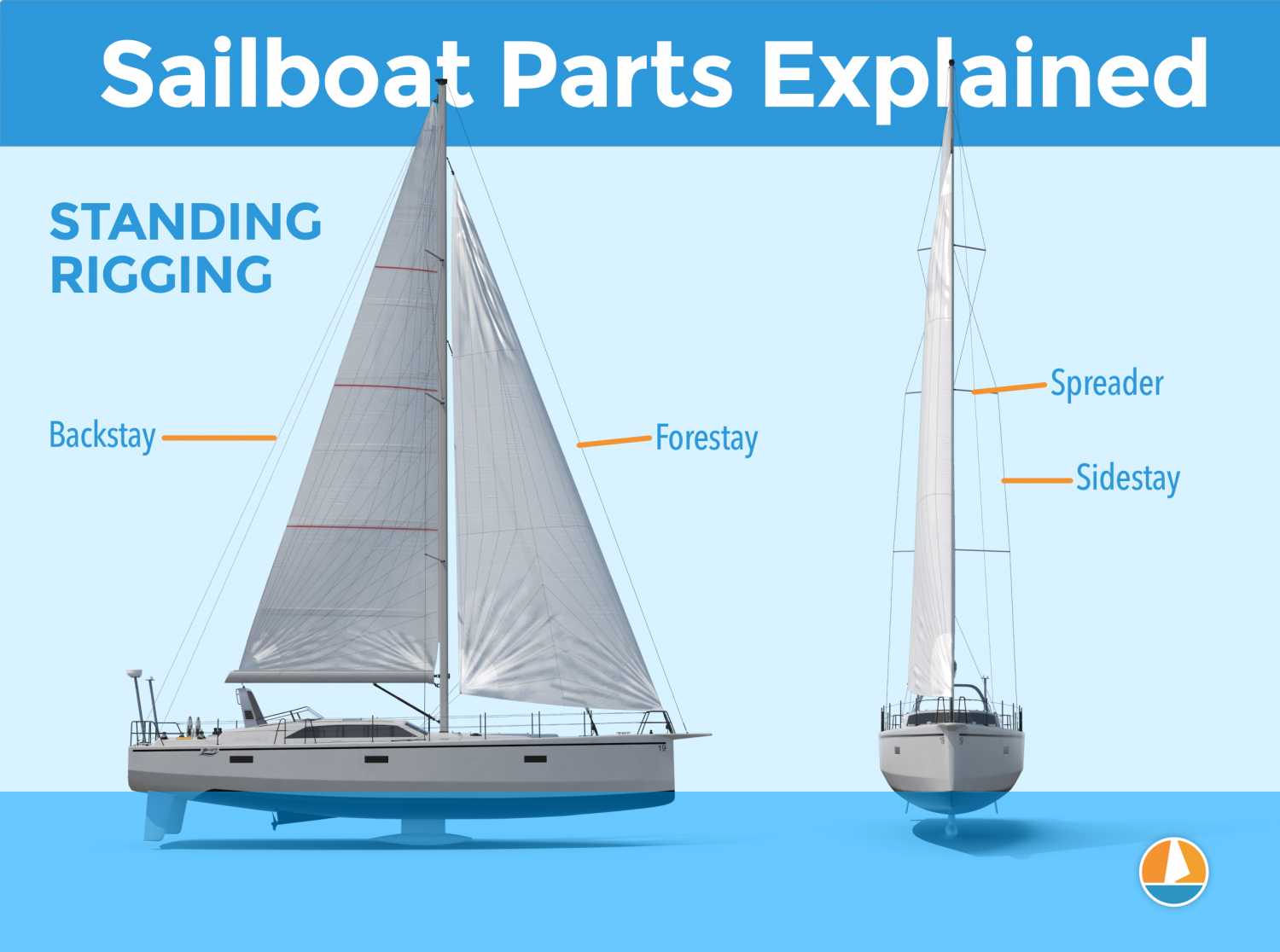

Here are the different parts that belong to the standing rigging:

- Forestay or Headstay - Line or cable that supports the mast and is attached to the bow of the boat. This is often a steel cable.

- Backstay - Line or cable that supports the mast and is attached to the stern of the boat. This is often a steel cable.

- Sidestay or Shroud - Line or cable that supports the mast from the sides of the boat. Most sailboats use at least two sidestays (one on each side).

- Spreader - The sidestays are spaced to steer clear from the mast using spreaders.

Running Rigging: different words for rope

Ropes play a big part in sailing, and especially in control over the sails. In sailboat jargon, we call ropes 'lines'. But there are some lines with a specific function that have a different name. I think this makes it easier to communicate with your crew: you don't have to define which line you mean. Instead, you simply shout 'mainsheet!'. Yeah, that works.

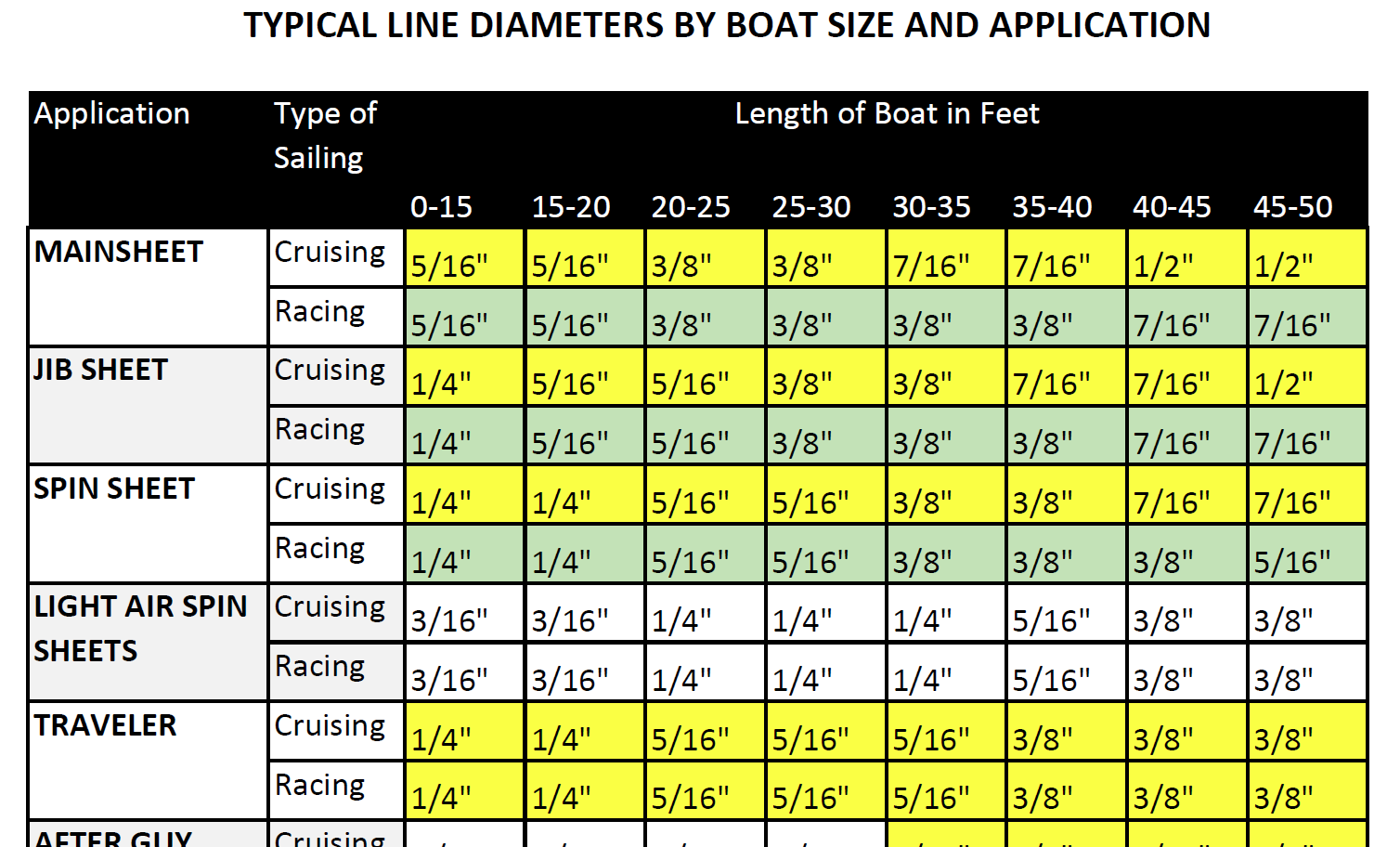

Running rigging consists of the lines, sheets, and hardware that are used to control, raise, lower, shape and manipulate the sails on a sailboat. Rigging varies for different rig types, but since most sailboats are use a sloop rig, nearly all sailboats use the following running rigging:

- Halyards -'Halyard' is simply the nautical name for lines or ropes that are used to raise and lower the mainsail. The halyard is attached to the top of the mainsail sheet, or the gaffer, which is a top spar that attaches to the mainsail. You'll find halyards on both the mainsail and jib.

- Sheets - 'Sheet' is simply the nautical term for lines or ropes that are used to set the angle of the sail.

- Mainsheet - The line, or sheet, that is used to set the angle of the mainsail. The mainsheet is attached to the Mainsheet traveler. More on that under hardware.

- Jib Sheet - The jib mostly comes with two sheets: one on each side of the mast. This prevents you from having to loosen your sheet, throwing it around the other side of the mast, and tightening it. The jib sheets are often controlled using winches (more on that under hardware).

- Cleats are small on-deck hooks that can be used to tie down sheets and lines after trimming them.

- Reefing lines - Lines that run through the mainsail, used to put a reef in the main.

- The Boom Topping Lift is a line that is attached to the aft (back) end of the boom and runs to the top of the mast. It supports the boom whenever you take down the mainsail.

- The Boom Vang is a line that places downward tension on the boom.

There are some more tensioning lines, but I'll leave them for now. I could probably do an entire guide on the different sheets on a sailboat. Who knows, perhaps I'll write it.

This is a new segment, that I didn't mention before. It's a bit of an odd duck, so I threw all sorts of stuff into this category. But they are just as important as all the other parts. Your hardware consists of cleats, winches, traveler and so on. If you don't know what all of this means, no worries: neither did I. Below, you'll find a complete overview of the different parts.

Deck Hardware

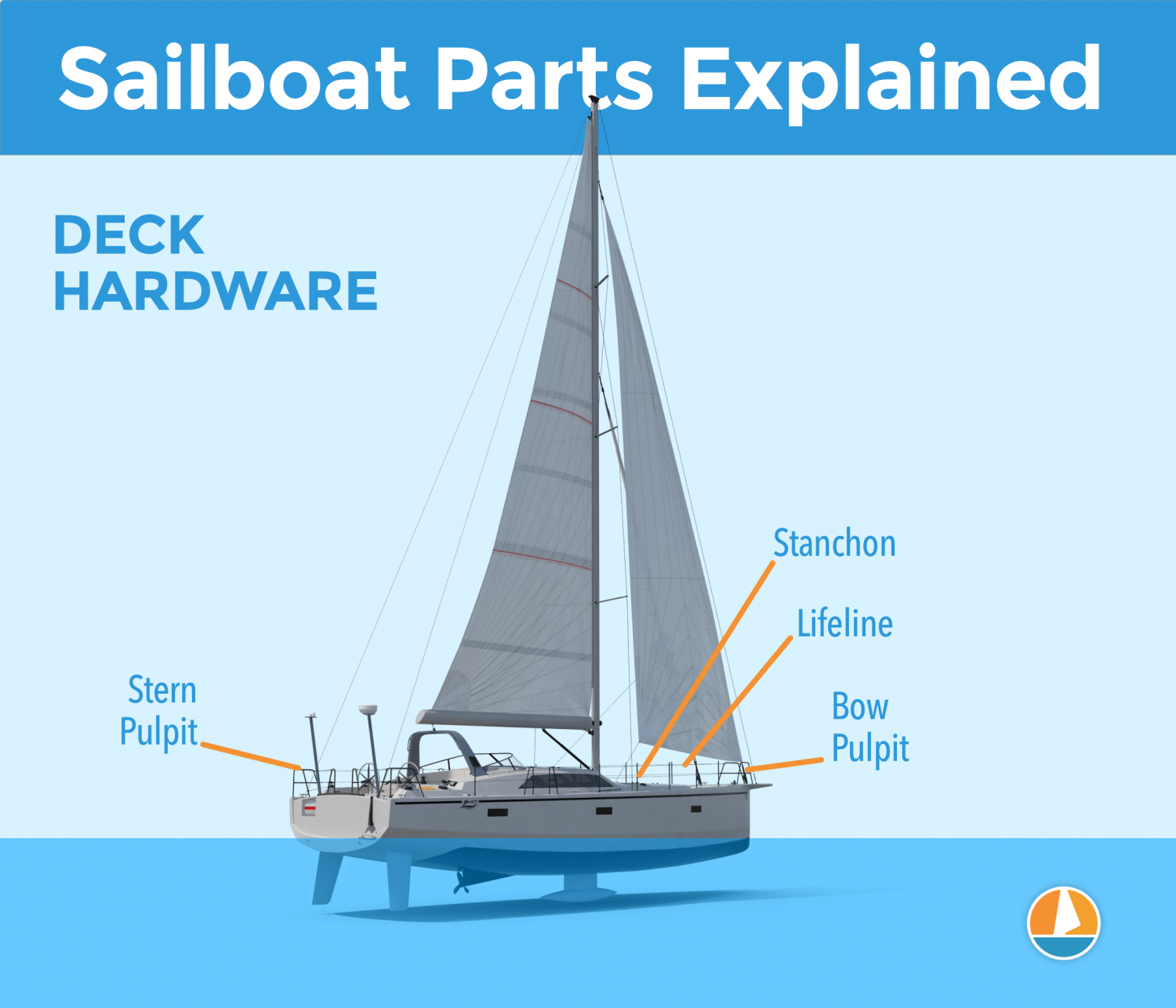

Just a brief mention of the different deck hardware parts:

- Pulpits are fenced platforms on the sailboat's stern and bow, which is why they are called the bow pulpit and stern pulpit here. They typically have a solid steel framing for safety.

- Stanchons are the standing poles supporting the lifeline , which combined for a sort of fencing around the sailboat's deck. On most sailboats, steel and steel cables are used for the stanchons and lifelines.

Mainsheet Traveler

The mainsheet traveler is a rail in the cockpit that is used to control the mainsheet. It helps to lock the mainsheet in place, fixing the mainsails angle to the wind.

If you're interested in learning more about how to use the mainsheet traveler, Matej has written a great list of tips for using your mainsheet traveler the right way . It's a good starting point for beginners.

Winches are mechanical or electronic spools that are used to easily trim lines and sheets. Most sailboats use winches to control the jib sheets. Modern large sailing yachts use electronic winches for nearly all lines. This makes it incredibly easy to trim your lines.

You'll find the compass typically in the cockpit. It's the most old-skool navigation tool out there, but I'm convinced it's also one of the most reliable. In any way, it definitely is the most solid backup navigator you can get for the money.

Want to learn how to use a compass quickly and reliably? It's easy. Just read my step-by-step beginner guide on How To Use a Compass (opens in new tab .

Chartplotter

Most sailboats nowadays use, besides a compass and a map, a chartplotter. Chartplotters are GPS devices that show a map and a course. It's very similar to your normal car navigation.

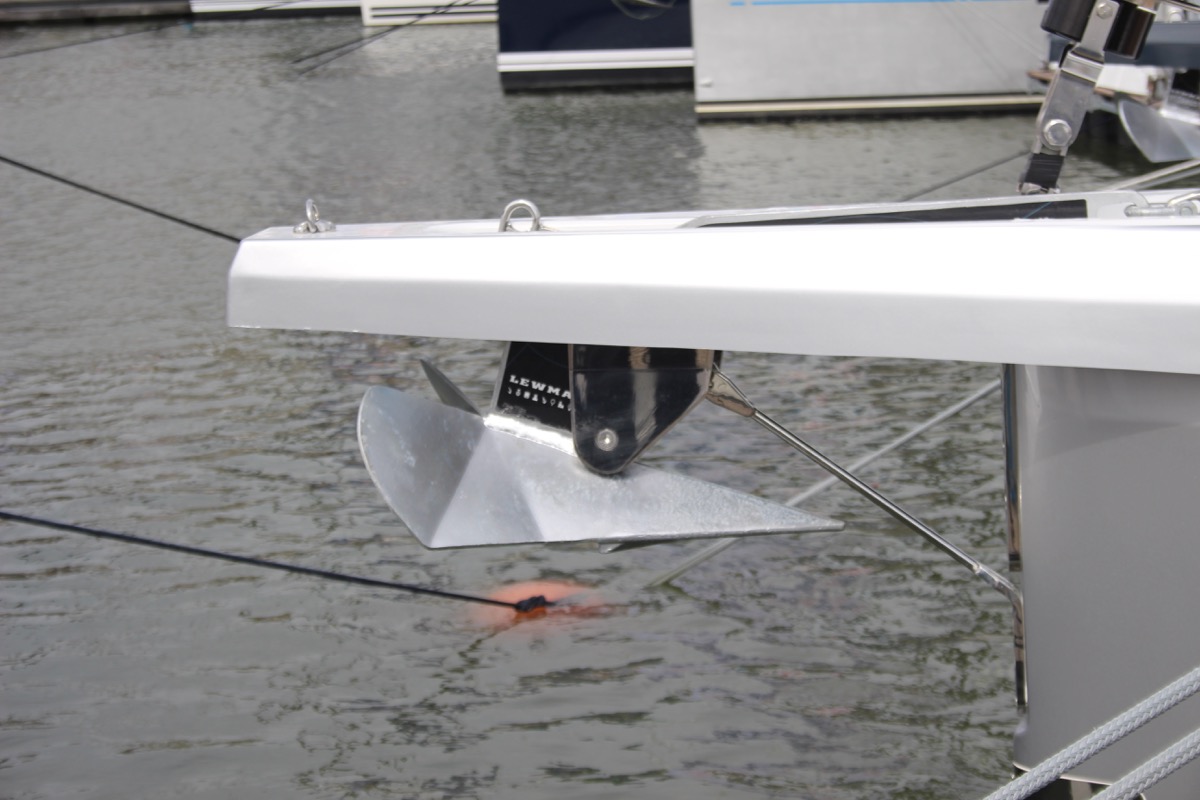

Outboard motor

Most sailboats have some sort of motor to help out when there's just the slightest breeze. These engines aren't very big or powerful, and most sailboats up to 32' use an outboard motor. You'll find these at the back of the boat.

Most sailboats carry 1 - 3 anchors: one bow anchor (the main one) and two stern anchors. The last two are optional and are mostly used by bluewater cruisers.

I hope this was helpful, and that you've gained a good understanding of the different parts involved in sailing. I wanted to write a good walk-through instead of overwhelming you with lists and lists of nautical terms. I hope I've succeeded. If so, I appreciate any comments and tips below.

I've tried to be as comprehensive as possible, without getting into the real nitty gritty. That would make for a gigantic article. However, if you feel I've left something out that really should be in here, please let me know in the comments below, so I can update the article.

I own a small 20 foot yacht called a Red witch made locally back in the 70s here in Western Australia i found your article great and enjoyed reading it i know it will be a great help for me in my future leaning to sail regards John.

David Gardner

İ think this is a good explanation of the difference between a ”rope” and a ”line”:

Rope is unemployed cordage. In other words, when it is in a coil and has not been assigned a job, it is just a rope.

On the other hand, when you prepare a rope for a specific task, it becomes employed and is a line. The line is labeled by the job it performs; for example, anchor line, dock line, fender line, etc.

Hey Mr. Buckles

I am taking on new crew to race with me on my Flying Scot (19ft dingy). I find your Sailboat Parts Explained to be clear and concise. I believe it will help my new crew learn the language that we use on the boat quickly without being overwhelmed.

PS: my grandparents were from Friesland and emigrated to America.

Thank you Shawn for the well written, clear and easy to digest introductory article. Just after reading this first article I feel excited and ready to set sails and go!! LOL!! Cheers! Daniel.

steve Balog

well done, chap

Great intro. However, the overview diagram misidentifies the cockpit location. The cockpit is located aft of the helm. Your diagram points to a location to the fore of the helm.

William Thompson-Ambrose

An excellent introduction to the basic anatomy and function of the sailboat. Anyone who wants to start sailing should consider the above article before stepping aboard! Thank-you

James Huskisson

Thanks for you efforts mate. We’ve all got to start somewhere. Thanks for sharing. Hoping to my first yacht. 25ft Holland. Would love to cross the Bass Strait one day to Tasmania. 👌 Cheers mate

Alan Alexander Percy

thankyou ijust aquired my first sailboat at 66yrs of age its down at pelican point a beautifull place in virginia usa my sailboat is a redwing 30 if you are ever in the area i wouldnt mind your guidance and superior knowledge of how to sail but iam sure your fantastic article will help my sailboat is wings 30 ft

Thanks for quick refresher course. Having sailed in California for 20+ years I now live in Spain where I have to take a spanish exam for a sailboat license. Problem is, it’s only in spanish. So a lot to learn for an old guy like me.

Very comprehensive, thank you

Your article really brought all the pieces together for me today. I have been adventuring my first sailing voyage for 2 months from the Carolinas and am now in Eleuthera waiting on weather to make the Exumas!!! Great job and thanks

Helen Ballard

I’ve at last found something of an adventure to have in sailing, so I’m starting at the basics, I have done a little sailing but need more despite being over 60 life in the old dog etc, thanks for your information 😊

Barbara Scott

I don’t have a sailboat, neither do l plan to literally take to the waters. But for mental exercise, l have decided to take to sailing in my Bermuda sloop, learning what it takes to become a good sailor and run a tight ship, even if it’s just imaginary. Thank you for helping me on my journey to countless adventures and misadventures, just to keep it out of the doldrums! (I’m a 69 year old African American female who have rediscovered why l enjoyed reading The Adventures of Robert Louis Stevenson as well as his captivating description of sea, wind, sailboat,and sailor).

Great article and very good information source for a beginner like me. But I didn’t find out what I had hoped to, which is, what are all those noisy bits of kit on top of the mast? I know the one with the arrow is a weather vane, but the rest? Many thanks, Jay.

Louis Cohen

The main halyard is attached to the head of the mainsail, not the to the mainsheet. In the USA, we say gaff, not gaffer. The gaff often has its own halyard separate from the main halyard.

Other than that it’s a nice article with good diagrams.

A Girl Who Has an Open Sail Dream

Wow! That was a lot of great detail! Thank you, this is going to help me a lot on my project!

Hi, good info, do u know a book that explains all the systems on a candc 27,

Leave a comment

You may also like, guide to understanding sail rig types (with pictures).

There are a lot of different sail rig types and it can be difficult to remember what's what. So I've come up with a system. Let me explain it in this article.

The Ultimate Guide to Sail Types and Rigs (with Pictures)

The Illustrated Guide To Boat Hull Types (11 Examples)

How To Live On a Boat For Free: How I'd Do It

How To Live on a Sailboat: Consider These 5 Things

- New Sailboats

- Sailboats 21-30ft

- Sailboats 31-35ft

- Sailboats 36-40ft

- Sailboats Over 40ft

- Sailboats Under 21feet

- used_sailboats

- Apps and Computer Programs

- Communications

- Fishfinders

- Handheld Electronics

- Plotters MFDS Rradar

- Wind, Speed & Depth Instruments

- Anchoring Mooring

- Running Rigging

- Sails Canvas

- Standing Rigging

- Diesel Engines

- Off Grid Energy

- Cleaning Waxing

- DIY Projects

- Repair, Tools & Materials

- Spare Parts

- Tools & Gadgets

- Cabin Comfort

- Ventilation

- Footwear Apparel

- Foul Weather Gear

- Mailport & PS Advisor

- Inside Practical Sailor Blog

- Activate My Web Access

- Reset Password

- Customer Service

- Free Newsletter

Catalina 270 vs. The Beneteau First 265 Used Boat Match-Up

Ericson 41 Used Boat Review

Mason 33 Used Boat Review

Beneteau 311, Catalina 310 and Hunter 326 Used Boat Comparison

Tips From A First “Sail” on the ICW

Tillerpilot Tips and Safety Cautions

Best Crimpers and Strippers for Fixing Marine Electrical Connectors

Thinking Through a Solar Power Installation

Polyester vs. Nylon Rode

Getting the Most Out of Older Sails

How (Not) to Tie Your Boat to a Dock

Stopping Mainsheet Twist

Fuel Lift Pump: Easy DIY Diesel Fuel System Diagnostic and Repair

Ensuring Safe Shorepower

Sinking? Check Your Stuffing Box

The Rain Catcher’s Guide

What Do You Do With Old Fiberglass Boats?

Boat Repairs for the Technically Illiterate

Boat Maintenance for the Technically Illiterate: Part 1

Whats the Best Way to Restore Clear Plastic Windows?

Giving Bugs the Big Goodbye

Galley Gadgets for the Cruising Sailor

Those Extras you Don’t Need But Love to Have

What’s the Best Sunscreen?

UV Clothing: Is It Worth the Hype?

Preparing Yourself for Solo Sailing

How to Select Crew for a Passage or Delivery

R. Tucker Thompson Tall Ship Youth Voyage

On Watch: This 60-Year-Old Hinckley Pilot 35 is Also a Working…

On Watch: America’s Cup

On Watch: All Eyes on Europe Sail Racing

Dear Readers

- Boat Maintenance

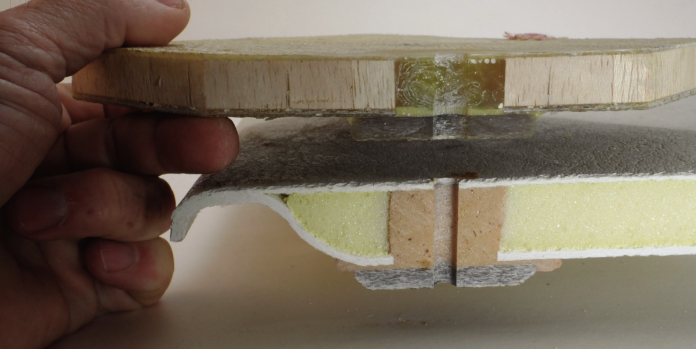

Bulletproof Sailboat Deck Hardware

Rock-solid deck hardware installation begins with a tightly sealed core.

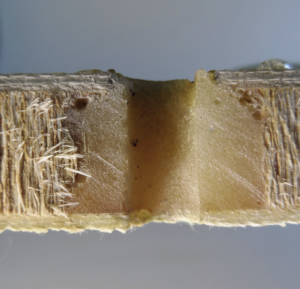

Installing new hardware on a cored deck means sealing the core around every penetration. Skip this step and water will eventually seep between the skins. Balsa will rot, and repeated freezing and thaw cycles can turn foam core to mush and cause delamination.

The typical solution is to drill an oversized hole, fill the cavity with epoxy, and redrill as needed. But this method is not without drawbacks and shortcomings:

• Some people have become sensitized to epoxy, with symptoms ranging from skin irritation to full-on shock.

• Epoxy has limited tolerance for moisture; yes, you should dry the core first, but that doesn’t always happen.

• If you use fast-curing epoxy in warm weather, it can exotherm and boil out.

• If you use slow-curing epoxy, it might not cure overnight.

And then there are practical problems with the traditional method. Working from the top, you must over-drill the hole to get enough room for the epoxy to enter and to allow air to escape. This requires removing more of the top skin, creating a larger scar to disguise should you decide to relocate the gear. Completely filling a hole on a vertical surface requires a bit of magic. And then there’s the nature of the epoxy plug, which can become brittle and crack over time. Unless the plug is fully supported by a backing plate, it can be pushed out of position, again exposing the core to moisture.

TRADITIONAL METHOD

Although epoxy is our “go-to” material, and the traditional method is well proven, we believe there are better ways.

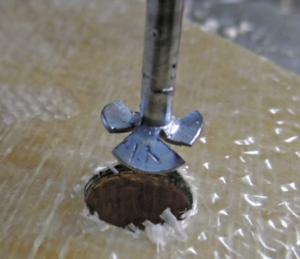

In the traditional method, a hole is drilled through the top skin only, at least as large as the fastener and large enough to admit the core removal tool of your choice. The core is removed by moving a cutter up and down between the core skins and around the circumference of the hole until the core is dust. You need to pay special attention to the insides of the top and bottom skins, because that top-to-bottom bond is what helps maintain strength in the laminated structure.

We like to use a bent roofing nail. It removes chips, produces a deep cavity, and cuts smoothly. After blowing out the chips, the hole is filled with slow cure epoxy (in warm temperatures, fast-cure will exotherm, creating bubbles and a poor seal).

The hole is then re-drilled through both skins to fit the fastener, and the hardware bedded and installed (see “ Trouble Free Deck Hardware Installation ,” PS September 2013).

ADDING GLASS REINFORCEMENT

You can protect against cracking with reinforcing fiberglass. Adding glass fibers is particularly useful when installing or repairing screws or other self-tapping fasteners.

Inject about 50 percent of the epoxy first. This will help wet out the cloth. Using a large cable tie, stiff wire, or similar tool, push 3/4” x 2” strips of 6-ounce fiberglass cloth into the epoxy-saturated hole. You can fit 2-4 strips in the smallest holes and 3-6 strips into larger fastener holes. Only a few strips are needed for crack control, but for future screw holes, cram as many as you can. Don’t use fiberglass mat, roving, or biaxial cloth, these weaves don’t conform to the hole as easily as cloth, and they are harder to wet out. Follow up with more epoxy to fill the space, gently poking the glass to help the air release (see “ A Stronger Screw Hole Repair ,” PS May 2018”).

TECH GUIDE: CORE FILLER SPECIFICATIONS

| MANUFACTURER | PRODUCT* | TENSILE STRENGTH (PSI) | VISCOSITY AT 72°F IN CENTIPASCALS (CPA)* | COMMENTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CORE SEALING | ||||

| SYSTEM 3 | General purpose 2-part epoxy | 7,500 psi | 950 cPA | Add high-density filler and/or cloth if needed. |

| WEST SYSTEMS | 105/205 2-part epoxy | 7,800 psi | 975 cPA | Add high-density filler and/or cloth if needed. |

| WEST SYSTEMS | G-Flex 2-part epoxy | 3,440 psi | 15000 cPA | Tougher, better with damp surfaces. |

| GENERIC PASTE EPOXY | Generic thickened epoxy | 1,500-2,500 psi | Paste cPA | Weakened by micro air bubbles. Tougher. |

| PETTIT | Splash Zone 2-part epoxy | 4,100 psi | Paste cPA | Will bond wet. Low exotherm. |

| CORE REPAIR BY INJECTION | ||||

| SYSTEM 3 | Clear 2-part epoxy | 7,800 psi | 380 cPA | Penetrates well, good bond. |

| SYSTEM 3 | Rot Fix 2-part epoxy | 7,800 psi | 325 cPA | Penetrates well, good bond. |

| WEST SYSTEMS | 105/205 +5% acetone 2-part epoxy | 2,800 psi | 310 cPA | Solvent must be able to evaporate. |

| GORILLA GLUE | Original 1-part polyurethane | 600-4,250 | 3000 (thins as foam) | Expands and foams in moisture. |

| *Epoxy adhesives thin with heat, but also gel faster. Slow hardeners delay exotherm in temperatures below 90°F, but slow hardeners are also more vulnerable to moisture. |

One wouldn’t naturally think that a fastener hole would be prone to exothem. The volume seems so small. The trouble is that the core insulates the hole, preventing the epoxy from shedding heat. Below 70°F and out of the sun, a fast-cure epoxy like West Systems 105/205 will work for this job. In warmer temperatures, or in the sun, the epoxy will become boiling, and the plug will be more foam than epoxy. Slow hardener (such as West Systems 206) is the standard recommendation, but in cool weather it may not be fully cured until the next day, delaying work.

Toughened epoxies, such as G-Flex, and underwater epoxies do not have the same tendency to exotherm in small holes. They cure more slowly and give off less heat in the process. They also have a reduced tendency to crack. When using the traditional, “core-carve” method for filling screw holes, G-Flex performed well in our bench tests. Field tests are still ongoing. Underwater epoxies are too thick to work with the traditional method, but we have tested them using what we call the inside-core method.

SPECS: BOND STRENGTH

| ADHESIVE | SECONDARY BOND TENSILE STRENGTH |

|---|---|

| VINYLESTER | 500 psi |

| POLYESTER | 350 psi |

| EPOXY | 2,000 psi |

POLYESTER AND VINYLESTER RESINS

Polyester and vinylester shrink during cure, and the secondary bond—the bond an already cured skin—with the outer skins is about 4-6 times weaker for polyester, and 2-4 time weaker for vinylester. This bond is insufficient, especially when compared to the advantages of epoxy.

RIGID POLYURETHANES (GORILLA GLUE, TITEBOND, ETC.)

The main advantage of rigid polyurethane glue is its moisture tolerance. Previously, we learned that a deteriorated deck can be stiffened by injecting adhesives or foam (see “ Can Glue Injection Save a Rotten Core? ” PS July 2020).

We continue to recommend complete core replacement as the best way to rebuild damaged decks (“ Step-by-Step Deck Core Repair ,” PS August 2020, and “ Deck Core Repair from Underneath ,” PS February 2022). However, while exploring the glue-injection method, we found the Original Gorilla Glue performed better than epoxy in some circumstances.

We’ve since become fans of the glue, using it for several small repairs and in situations where tearing the boat apart was either too complex or not warranted. We wondered if Gorilla Glue could do double duty when sealing new holes for fasteners. Could it seal the core against water intrusion and stiffen up a larger area of deck to resist compression loads?

The answer is yes—with limitations. Gorilla glue foams and expands when reacting with water, so you have to use it differently than you would epoxy. The foaming is inherent to this type of glue.

Assuming you’ve carved out the core using the traditional method, you pump or pour the glue slowly into the hole allowing air to bubble out. Within 5 to 10 minutes, the glue will begin to foam and expand.

Don’t let the foaming glue spill back out, force it back into the core by plugging the holes with wooden dowels. This will push the glue into voids. Leave the dowels in place until the glue has finished expanding, but pull them out with a set of pliers before the glue cures (2-4 hours). Later, use epoxy to fill the dowel’s impressions. This method works when stiffening soft spots in dry core.

However, the method did not fare as well during our test with damp core. For that test, we made a plug in a balsa core section that had been soaked in water for two weeks and then allowed to dry for 8 hours. In this case, the foaming was extensive and the resulting plug was porous and weak, much like the core material itself.

With dry balsa, however, the Gorilla Glue plugs had physical properties similar to epoxy plugs, with minimal foaming. As with epoxy, these plugs could also be reinforced with fiberglass.

There are other polyurethanes that foam less with moisture (Titebond III). However, foaming cannot be entirely avoided. For this reason, we’d avoid polyurethane glues for sealing fastener holes in core.

CONCLUSIONS

The traditional method remains our “go to” for routine fastener installations. If we’re going to be installing a large backing plate, the inside core method is faster, easier, and stronger, when the entire process is considered. It is perfect for winches and windlasses. If access is sufficient, we also like this method for repairing leaking fasteners (the old, failed plug is easily removed) and for installing new fasteners in deteriorated decks. We get a good look at the core, the reinforced plug is larger, and the backing plate can be oversized to firm things up.

If you have multiple deck holes to seal, have access to the inside of the holes, and will be installing backing plates, it may be best to tackle the whole job from inside. This method will also work from the outside if you are installing a mounting pad large enough to generously cover the hole you will make in the core. It is handy when placing fasteners through plywood core, since plywood core is difficult to remove with a bent nail.

We do not recommend this method for large through-hull fittings. Too much of the inside skin is removed.

• Drill a ¼-inch hole through from the top side to guide the hole saw. You will redrill to the fastener size later.

• Using a hole saw, drill a ¾-inch (or larger as needed) hole through the inside skin and core, using the initial hole as a guide. Use a depth stop to avoid damaging the top skin.

• Pop out the core and clean out the hole using a bent roofing nail or small chisel. You do not have to carve core from under the edge of the inside skin, just clean the edges of the hole and underside of the top skin.

• Make a backing plate with a ¼-inch center hole (the hole is optional but helpful). Round the corners at least 1-inch radius and taper. Center over the hole and mark the outline with a pencil.

• Fill the hole with thickened epoxy, leaving it slightly proud. Thinly butter the backing plate and the backing plate contact area, which should be marked in pencil.

• You can also reinforce the plug with glass fiber, but don’t try laying in glass cloth, roving, or mat; the thickened epoxy will never wet it out. Instead, just work in a small handful of chopped strands, adding them between layers. You don’t need much fiber to control cracks, so focus on even distribution.

• If the core is damp, let it dry. If this is impractical, consider using Pettit Splash Zone underwater epoxy. It bonds to damp surfaces, will cure underwater, and has suitable strength and hardness.

• Beware the exotherm. Thickened epoxies exotherm slower than straight epoxy, because of the mass added by the filler, but in warm conditions (over 80°F) use a slow hardener. Waterproof epoxies are already slow-cure formulas.

• Press the plate into place, securing with a waxed bolt (can be smaller than 1/4-inch) through the center. Remove this as soon as the epoxy gels. Using the epoxy that squeezes out, form a rounded fillet between the skin and the backing plate.

• After curing, redrill the center hole to fit the fastener.

The larger drilled hole is easier to clean out, the hole is easy to fill with epoxy putty, the plug is larger, better bonded and better supported, and the backing plate is now an integral part of the hull. Yes, you lose a small amount of skin on the inside, but that’s more than made up for by the increased efficiency of a well-bonded backing plate. We think this is a better method for sealing common through-bolts.

Core weakened or damaged by water intrusion—usually due to poor hardware installation practices—is a common problem in older boats. In recent years, we’ve conducted a series of related tests to determine effective repair and prevention methods.

• “Cored Hull Construction, Does High Tech Mean High Quality?” ( PS October 2007 )

• “Boat Clinic: Minor Repair to Cored Decks” ( PS Online March 2011 )

•“Through-bolting Fiberglass: An Inquiry into Failure Modes” ( PS June 2013 )

• “A Stronger Screw Hole Repair” ( PS May 2018 )

• “How Big Does a Backing Plate Need to Be?” ( PS August 2016 )

• ‘Step-by-Step Deck Core Repair” ( PS July 2020 )

• “Can Glue Injection Fix Rotten Core?” ( PS July 2020 )

•“Deck Core Repair, from Underneath” ( PS February 2022 )

Here we compare filler materials used to seal core from water intrusion.

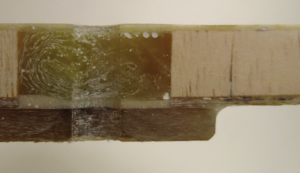

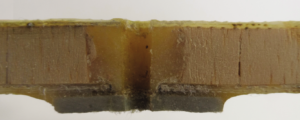

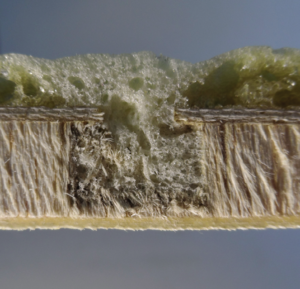

1.Gorilla glue fails to form a solid plug in damp core. The filler is porous and weak, similar to that of a foam core.

2.Dry balsa core sealed with 105/205 Epoxy is rock solid and well bonded.

3.1:1 pre-thickened epoxy was used here with foam core. It is okay to have a few isolated bubbles. The important thing is a good bond at the top and bottom.

4.General purpose two-part epoxy forms a tight bond in this photo of an epoxy plug in balsa.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

_An Allen Wrench to Remove Core_ When I installed my fittings on Prestissimo, a 42′ sloop, I drilled a hole sized for the bolt, down to, but not through, the interior skin. Then I used a Allen wrench, with the short end sharpened like a knife, and the long end in a drill, to chop up the foam core. I vacuumed out the foam pieces, and used a squeeze bottle with an aluminum tube sticking out of the nozzle to fill the void with epoxy from the bottom up. After drilling out the holes I installed the fittings, bedded the backing plates in epoxy, and tightened the bolts which were sprayed with mold release. Finally the fittings and bolts were removed, the holes were cleaned (if necessary), and everything was reinstalled with a generous coating of BoatLife under the fitting and all around the bolt. She has been sailing for 18 years and not a single fitting has leaked!

My preference for holes and fillets is milled glass fibers. In the jar/tub, it’s like lint. After it sets in epoxy you can beat on it with a 3# hammer for a long time before it starts to crack.

It stiffens the epoxy well enough that it can often be used vertically without sagging.

I thought we had put the ‘bent nail’ issue to bed decades ago. There are so many useful Dremel attachments out there, anything else is a crime against efficiency and pride in your work. Dremel 115, 196 or 199, Countersink, and bed with Butyl tape (isobutylene-isoprene, not mastic).

LEAVE A REPLY Cancel reply

Log in to leave a comment

Latest Videos

Super Shallow Draft Sailboat: The Leeboard Sharpie

Hans Christian 41T – Boat Review

Seven dead after superyacht sinks off Sicily. Was the crew at...

What’s the Best Sailboats for Beginners?

Latest sailboat review.

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell My Personal Information

- Online Account Activation

- Privacy Manager

- Find A School

- Certifications

- North U Sail Trim

- Inside Sailing with Peter Isler

- Docking Made Easy

- Study Quizzes

- Bite-sized Lessons

- Fun Quizzes

- Sailing Challenge

Parts of a Sailboat – The Deck

By: Zeke Quezada, ASA Learn To Sail , Sailboats

Understanding the deck of a sailboat is all part of learning to sail. Essentially, the deck of a boat is both your office and your supply cabinet. This is because many of the tools required to sail a vessel are on the deck.

Sailboats come in many shapes, sizes, and forms to meet the needs of sailors with various desires and ambitions. They also reflect the styles and ideas of their designers and builders and are considered by some sailors to be an art form. The illustrations below depict a boat about 33 feet long of fairly typical design above and below deck and fitted with basic systems commonly found on cruising boats.

The boat we are describing is typical of a boat you may be using as part of ASA 103 Basic Coastal Cruising — it’s more involved and some parts may not be found on a smaller daysailing vessel. However, there’s a lot more to a cruising boat than a cockpit and cuddy cabin. You can walk around on it, on deck, and below. And it has a few more features for which you’ll have to learn the nautical names.

Parts of the Deck of a Sailboat - Cruising Vessel

The Helm Smaller daysailers used for ASA Basic Keelboat courses often have a tiller; this boat has a steering wheel. While it’s possible to steer this big of a boat with a tiller, and many sailors prefer the feel and response it gives when sailing, the tiller needed to provide sufficient leverage would be quite long. The wheel offers the same or even more leverage while taking up much less space in the cockpit — much of the linkage system that connects it to the rudder is beneath the cockpit.

The Cockpit The cockpit of a cruising sailboat serves as the command center and focal point of activity while sailing. It is typically located in the recessed area of the deck where the helmsman sits or stands, and it often features storage lockers under the seats. The functionality of the cockpit is essential for helming, sail trimming, watchkeeping, and other sailing activities.

Modern boat designs have prioritized bigger, taller, and more comfortable living quarters over the functionality of the cockpit. As a result, cockpit ergonomics involve more than comfortable seating and coaming angles. Wide-beam boats benefit from a large diameter wheel, allowing the helmsman to steer on the windward rail where sight lines are unimpeded by a dodger, mast, or headsail.

Some boats have every sail-control line led to the cockpit, which requires additional blocks or sheaves to be added to the running rigging system.

The cockpit is self-bailing — it’s high enough above the waterline that any water that gets into it can drain overboard by gravity. Water drains through scuppers (they look like large bathtub drains) in the aft corners of the cockpit well.

Sailing is not all tacking and jibing; the cockpit also serves as the boat’s porch, lounge, and dining room. The seats are designed to provide support and comfort when sailing and at rest.

Cockpit Stowages Daysailers carry a fair amount of ancillary gear — dock lines, fenders, and safety gear — and a boat equipped for cruising carries a great deal more. All this stuff has to go somewhere so it’s not underfoot while the boat’s sailing, so a lot of it goes in the cockpit lockers.

A hatch in the cockpit seat typically opens to reveal a deep locker. Such a locker is large enough to hold lots of gear, including an extra sail or two. Keeping it organized can be challenging but necessary, not so that you can find a spare line in a hurry but because often the same locker also provides access to some critical fixed equipment. That equipment may include the engine and the steering gear. Another shallow locker may exist in the cockpit, but this one is shallow because the space below is used as part of the living quarters. Finally, at the helm, you may find a hatch or two that provide access to the steering gear and other systems.

Obstacles on the Deck Obstacles are inevitable on the deck of a sailboat. When navigating on the deck, make sure to always reserve a hand for the boat to ensure your safety, maintaining three points of contact. If sailing, the safest path forward is along the windward side. Always use the handrails to keep your body closer to the boat.

Sidedeck Your first obstacle when leaving the cockpit to go forward on the deck is the cockpit coaming, which extends aft of the trunk cabin, the area of the deck that’s raised to provide headroom in the cabin below.

Stepping over the cockpit coaming brings you onto the side deck, which runs between the trunk cabin and the outside edge of the deck (which is often referred to as the rail because of the toerail attached there to provide secure footing).

Just inside the toerail are the stanchions that support the lifelines.

As you move forward, you will encounter the shrouds, the wires that support the mast laterally. They attach to the deck at the chainplates which carry the forces generated by the sails into the structure of the hull.

Between the lower end of each wire shroud and its chainplate is a turnbuckle, which is used to tension the shroud by adjusting its length. A clevis pin connects the turnbuckle to the chainplate and a cotter pin passed through a hole on the end of the clevis pin prevents the clevis pin from backing out. Cotter pins are also fitted through the screws in the turnbuckles so they cannot unscrew and loosen.

Foredeck When you walk forward of the mast, you come to the foredeck. Most modern sailboats have roller-furling sails, so you will not be changing a headsail on the foredeck, but you will still utilize this space when anchoring and docking.

Fairleads on each side of the bow direct docklines to two large mooring cleats mounted on the deck.

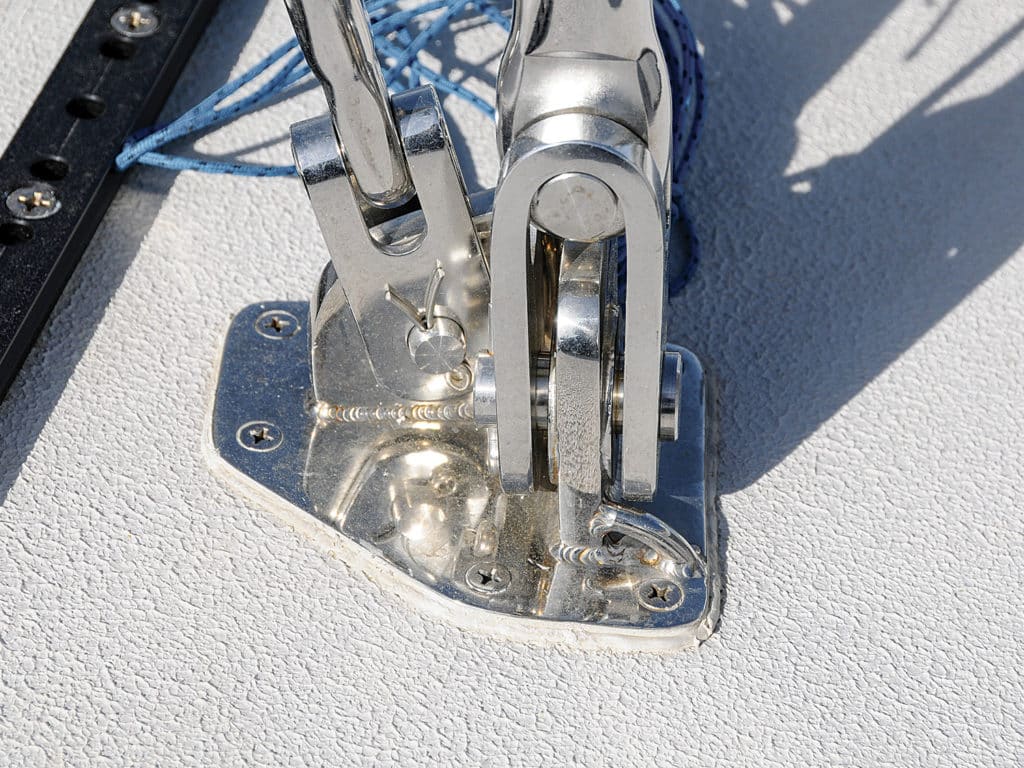

The anchor can be found on the foredeck and is usually stowed on a stemhead fitting. This setup makes for a much easier deployment of the anchor. The stemhead fitting is a hefty stainless-steel fabrication that incorporates a roller fairlead for the anchor rode and the chainplate for the forestay. A hatch in the foredeck covers the anchor locker where the rode is stowed ready for use.

WANT TO LEARN MORE?

READ: Parts of a Sailboat — The Sails

READ: Parts of a Sailboat — The Keel

Related Posts:

- Learn To Sail

- Mobile Apps

- Online Courses

- Upcoming Courses

- Sailor Resources

- ASA Log Book

- Bite Sized Lessons

- Knots Made Easy

- Catamaran Challenge

- Sailing Vacations

- Sailing Cruises

- Charter Resources

- International Proficiency Certificate

- Find A Charter

- All Articles

- Sailing Tips

- Sailing Terms

- Destinations

- Environmental

- Initiatives

- Instructor Resources

- Become An Instructor

- Become An ASA School

- Member / Instructor Login

- Affiliate Login

× You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

We Ship Worldwide! | FREE SHIPPING! for US Continental orders over $99. Click for details.

Shopping Cart

Your cart is currently empty..

FREE SHIPPING! for US Continental orders over $99 click for details

Furlers & Headsail Foils

Sailboat Parts & Sailing Equipment

General Information

- Free Shipping Offer

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Price Matching

- Privacy Policy

- Shipping & Returns - USA Orders

- Shipping Info - International Orders

- Affiliate Program

- Gift Certificates

- WholeSAILPRO Program

- Brand Ambassadors

- Our Store: Henri-Lloyd North America

Corporate Address

- 2820 Scherer Dr. Ste 240 St. Petersburg, FL US, 33716

CONNECT WITH US

Copyright © 2024 mauripro sailing llc..

Standing Rigging (or ‘Name That Stay’)

Published by rigworks on november 19, 2019.

Question: When your riggers talk about standing rigging, they often use terms I don’t recognize. Can you break it down for me?

From the Rigger: Let’s play ‘Name that Stay’…

Forestay (1 or HS) – The forestay, or headstay, connects the mast to the front (bow) of the boat and keeps your mast from falling aft.

- Your forestay can be full length (masthead to deck) or fractional (1/8 to 1/4 from the top of the mast to the deck).

- Inner forestays, including staysail stays, solent stays and baby stays, connect to the mast below the main forestay and to the deck aft of the main forestay. Inner forestays allow you to hoist small inner headsails and/or provide additional stability to your rig.

Backstay (2 or BS) – The backstay runs from the mast to the back of the boat (transom) and is often adjustable to control forestay tension and the shape of the sails.

- A backstay can be either continuous (direct from mast to transom) or it may split in the lower section (7) with “legs” that ‘V’ out to the edges of the transom.

- Backstays often have hydraulic or manual tensioners built into them to increase forestay tension and bend the mast, which flattens your mainsail.

- Running backstays can be removable, adjustable, and provide additional support and tuning usually on fractional rigs. They run to the outer edges of the transom and are adjusted with each tack. The windward running back is in tension and the leeward is eased so as not to interfere with the boom and sails.

- Checkstays, useful on fractional rigs with bendy masts, are attached well below the backstay and provide aft tension to the mid panels of the mast to reduce mast bend and provide stabilization to reduce the mast from pumping.

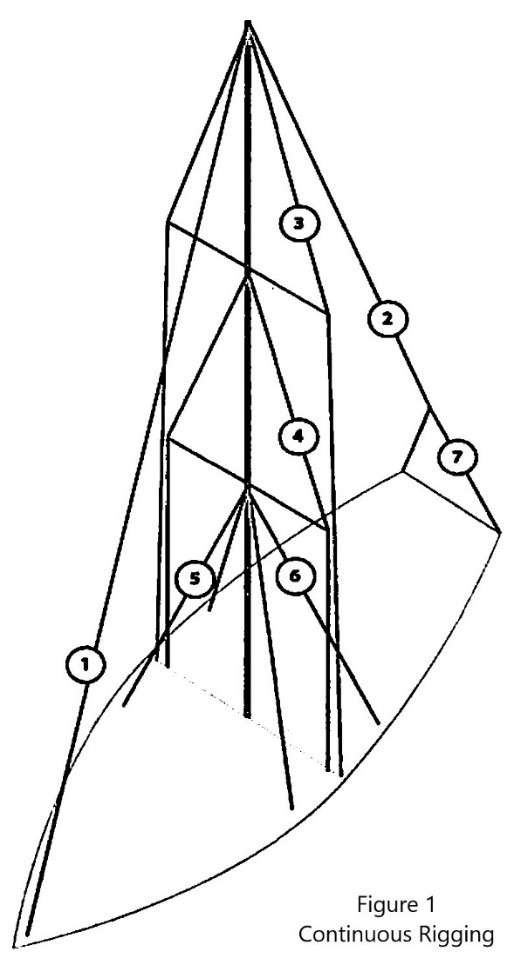

Shrouds – Shrouds support the mast from side to side. Shrouds are either continuous or discontinuous .

Continuous rigging, common in production sailboats, means that each shroud (except the lowers) is a continuous piece of material that connects to the mast at some point, passes through the spreaders without terminating, and continues to the deck. There may be a number of continuous shrouds on your boat ( see Figure 1 ).

- Cap shrouds (3) , sometimes called uppers, extend from masthead to the chainplates at the deck.

- Intermediate shrouds (4) extend from mid-mast panel to deck.

- Lower shrouds extend from below the spreader-base to the chainplates. Fore- (5) and Aft-Lowers (6) connect to the deck either forward or aft of the cap shroud.

Discontinuous rigging, common on high performance sailboats, is a series of shorter lengths that terminate in tip cups at each spreader. The diameter of the wire/rod can be reduced in the upper sections where loads are lighter, reducing overall weight. These independent sections are referred to as V# and D# ( see Figure 2 ). For example, V1 is the lowest vertical shroud that extends from the deck to the outer tip of the first spreader. D1 is the lowest diagonal shroud that extends from the deck to the mast at the base of the first spreader. The highest section that extends from the upper spreader to the mast head may be labeled either V# or D#.

A sailboat’s standing rigging is generally built from wire rope, rod, or occasionally a super-strong synthetic fibered rope such as Dyneema ® , carbon fiber, kevlar or PBO.

- 1×19 316 grade stainless steel Wire Rope (1 group of 19 wires, very stiff with low stretch) is standard on most sailboats. Wire rope is sized/priced by its diameter which varies from boat to boat, 3/16” through 1/2″ being the most common range.

- 1×19 Compact Strand or Dyform wire, a more expensive alternative, is used to increase strength, reduce stretch, and minimize diameter on high performance boats such as catamarans. It is also the best alternative when replacing rod with wire.

- Rod rigging offers lower stretch, longer life expectancy, and higher breaking strength than wire. Unlike wire rope, rod is defined by its breaking strength, usually ranging from -10 to -40 (approx. 10k to 40k breaking strength), rather than diameter. So, for example, we refer to 7/16” wire (diameter) vs. -10 Rod (breaking strength).

- Composite Rigging is a popular option for racing boats. It offers comparable breaking strengths to wire and rod with a significant reduction in weight and often lower stretch.

Are your eyes crossing yet? This is probably enough for now, but stay tuned for our next ‘Ask the Rigger’. We will continue this discussion with some of the fittings/connections/hardware associated with your standing rigging.

Related Posts

Ask the Rigger

Do your masthead sheaves need replacing.

Question: My halyard is binding. What’s up? From the Rigger: Most boat owners do not climb their masts regularly, but our riggers spend a lot of time up there. And they often find badly damaged Read more…

Selecting Rope – Length, Diameter, Type

Question: Do you have guidelines for selecting halyards, sheets, etc. for my sailboat? From the Rigger: First, if your old rope served its purpose but needs replacing, we recommend duplicating it as closely as possible Read more…

Spinlock Deckvest Maintenance

Question: What can I do to ensure that my Spinlock Deckvest is well-maintained and ready for the upcoming season? From the Rigger: We are so glad you asked! Deckvests need to be maintained so that Read more…

Pacific Sailboat Supply

- HARDWARE & RIGGING

- LINE & ROPE

ELECTRONICS

- APPAREL & GEAR

- ANCHORING & DOCKING

- DECK ORGANIZATION

FURLING SYSTEMS

SAIL HANDLING

- RIGGING & FITTINGS

- EMERGENCY RESCUE

- HARNESS & TETHERS

- RESCUE SUITS

- ANCHORING ROPE & CHAIN

- CRUISING LINE

- RACING & COMPETITION LINE

- INSTRUMENTS

- COMMUNICATION

- EPIRB & PLB

Your cart is empty

PACIFIC POINTS

OVER 10% OFF

UP TO 30% OFF

Over 15% off

DECK ORGANIZERS

UP TO 20% OFF

Up to 30% off

Featured Brands

Additional 10% off with promo code: LABORDAY2024

Harken Black Magic Blocks

Furling Systems

Deck Organizers

Sail Handling

Electronics

Mainsheet Systems

Safety Equipment

Anchoring & Docking

Apparel & Gear

Rigging & Fittings

Members automatically earn Pacific Points with every purchase. Simply log in, buy gear, and start accumulating points to cash in!

PRODUCT OF THE MONTH

Kong Roger Safety Harness

Kong Roger sailing and rescue harness is easy to adjust by the four special auto-locking buckles. Fitted with wide, comfortable and breathable paddings, one front belay loop, five gear loops arranged to avoid accidental snagging and a comfortable big rear loop for an easy handling of the operator during the different movement on the machine and on the ground.

High quality product, made in Italy! Tested at 150 kg (EN 813)

IN NEED OF TECHNICAL GUIDANCE?

Reach out with your question, and one of our staff members will get back to you shortly. Or, if you require immediate assistance, give us a call at 805-900-7282 during normal operating hours.

FEATURED CLASS

The 16′ skiff is a distinctly Australian high-performance dinghy, renowned for its three-person crew and impressive sailing capabilities. With a storied history spanning over a century, the class has evolved significantly over the years. Modern 16′ skiffs are equipped with two crew members on trapeze and feature large masthead asymmetrical spinnakers, enhancing their speed and agility. In Australia, the 16′ skiff is one of the most popular sailing boats, with active fleets in New South Wales and Queensland. There are currently over 80 boats registered across nine clubs, and regattas often see impressive turnouts of up to 45 boats. Many 16′ skiff clubs boast excellent facilities and are dedicated to supporting sailing across various smaller dinghy classes.

To contain costs and to provide closer racing, strict one design rules were introduced in 1997/98 for hull design and construction. A design by former skiff sailor, Craig Hughes, was accepted as being the most progressive and suitable to take the Class forward. The design rules also fixed the number of masts and sails which could be registered for the Australian Championship Series. Only two masts can be used and the number of sails is limited to three jibs, two main sails and two spinnakers. Boats utilise these sails in combinations to give different rig sizes which can be selected for optimal performance in different wind strengths.

16ft skiff specifications:

Hull Length: 4.88 m (16 ft)

Minimum Beam: 1520 mm

Maximum Beam: 1780 mm

Maximum Sail Area (Working): 22 m²

Sail Area (Spinnaker): Approx. 45 m²

Minimum Crew: 3

Pacific Sailboat Supply Gift Card

Set sail into adventure with the perfect gift for any sailing enthusiast! Our Pacific Sailboat Supply Gift Card is your gateway to a world of premium marine gear and accessories.

With access to over 300 top-tier brands, we’re dedicated to meeting all your maritime needs. Our site caters to racers and high-caliber sailors, so If you’re looking for something specific that’s not listed on our site, we’re more than happy to assist with custom orders at no extra service fee.

Give the gift of adventure, reliability, and maritime excellence with the Pacific Sailboat Supply Gift Card. It’s the ideal choice for birthdays, holidays, or any special event for the sailor in your life!

SUPPORT YOUTH SAILING

Click here to support junior programs

100% OF 2024 PROFIT FROM PACIFIC SAILBOAT SUPPLY BRANDED PRODUCT IS DONATED TO SUPPORT JUNIOR SAILING PROGRAMS.

KEEP ME UPDATED

Create an account to stay updated on new sailboat rigging, hardware, gear, and tech.

No products in the cart.

Sailing Ellidah is supported by our readers. Buying through our links may earn us an affiliate commission at no extra cost to you.

The Different Parts Of A Sailboat Explained

A sailboat consists of hundreds of parts, each with its specific term and function. From stern to bow, keel to mast, each part and its equipment plays a vital role in making the vessel seaworthy and able to sail.

In this guide, I’ll show you most of the components so you can better understand what they are and their function. We’ll begin with the main components, move to the basic features, and finish with our interior and equipment.

The main parts of a sailboat

The main parts of a sailboat are the key components that make it a vessel able to sail. You’ll notice that the structure has several distinct differences from powerboats.

We can categorize the main parts into the following:

- Hull: The main structure, or “body” part of a boat.

- Keel: The heavy fin at the bottom allows stability under sail.

- Rudder: The fin sticking down at the stern, allowing us to steer the vessel.

- Mast: The “spars” or “poles” holding the sails.

- Rigging: The standing rig is the wires that supports the mast. The running rigging is all the lines that control the sails.

- Boom: The horizontal spar supporting the bottom of the mainsail.

- Sails: The canvas used to harness the energy of the wind.

Let’s dig a bit deeper into each of the components.

Hull – The main structure

A sailboat’s hull is the vessel’s main body or structure. The shape is vital to the boat’s performance and stability, and you have probably seen boats in many different forms. Older vessels are typically narrow, with a rounded underbody and a small stern. Modern designs have a flatter belly and broad stern supporting dual helm stations.

One of the hull’s primary functions is to displace water and provide buoyancy to keep the boat afloat. The hull is also the structure that holds the vessel’s living compartments and all its equipment. The main structure must be strong enough to withstand the forces of the water and any rough weather conditions that Mother Nature might throw at it.

Fiberglass (GRP), steel, aluminum, and wood are the most commonly used hull materials, each with pros and cons.

You can learn more about hull materials and their strengths in this article .

A monohull is a type of sailboat that has a single hull. Monohulls are classified into two categories based on weight and shape: planing and displacement hulls.

Sailboats with more than one hull are called multihulls. There are two types of multihulls: catamarans, which have two, and trimarans, which have three. These boats are typically designed with planing hulls.

Keel – The fin under the boat

The keel of a sailboat is a structural fin that extends downward from the bottom of the hull. There are several types of keels, each with unique characteristics and advantages. They all serve the same fundamental purpose of stabilizing the boat when we sail by adding lateral resistance in the water and weight at the vessel’s bottom.

Standard keel designs include:

- Lifting Keel

Some sailboats have a retractable centerboard functioning as their keel, allowing them to take the boat into shallower areas.

Rudder – To steer the boat

The rudder is a flat surface that sits perpendicular to the waterline. It is connected to the boat by a pivot point, allowing it to swivel left and right. When the steering wheel or tiller is turned, the rudder moves, creating drag in the water causing the boat to turn. The size and shape of the rudder can vary depending on the size and type of boat.

The most commonly seen rudder designs:

- Full skeg-supported

- Semi skeg-supported

Skeg-supported rudders are structurally one of the most reliable and robust constructions, but they are less efficient than a balanced rudder performance-wise. Balanced rudders pivot around their vertical center, giving less drag in the water and higher maneuverability at the cost of being a more vulnerable construction.

Twin rudders are often seen on modern performance sailboats with a wide stern. When the sailboat heel over , the leeward rudder gets better track through the water than a single rudder placed at the vessel’s center line. Contrary to some misconceptions, they can’t be controlled individually, even if the boat has two steering wheels.

Mast and Rigging – Supporting the sails

The mast is the long vertical spar that extends upward from the deck of a sailboat and holds the sails. It is the tallest part of the boat and is typically made of wood, aluminum, or carbon fiber. The mast is held in place by stays and shrouds, which form the sailboat’s standing rigging.

Depending on the rig the boat is manufactured with, there are several different types of masts. For example, a sloop-rigged sailboat will have only one main mast, while a ketch-rigged vessel will have a smaller additional mizzen mast placed further aft from the main mast.

There are two types of rigging:

- The Standing rigging consists of the stays and shrouds that keep the mast or masts in place.

- The Running rigging is the lines we use to hoist, lower, and control the sails.

Pro Tip: “S par” is a general term for a pole made of a solid material like wood, metal, or composite and is used to support a boat’s sail. The mast, boom, spreaders, and poles are defined as spars.

Boom – Supporting the mainsail

The boom is a horizontal beam extending from the mast and supporting the mainsail’s tack and clew (bottom two corners). It is attached to the mast by a hinge called a Gooseneck .

We use the boom to control the shape and angle of the mainsail to optimize its efficiency and power. Some booms also have a Vang or Rod-Kicker installed to assist in trimming the mainsail.

Sails – The canvas used to harness the energy of the wind

Most vessels have at least two sails, depending on the rig type and boat setup.

The Mainsail flies behind the mast, on top of the boom. Although it may not always be the largest sail on the vessel, we commonly refer to it as “the main.”

The Headsail(s ), located in front of the mast, are often of different sizes and shapes, and many sailboats have more than one. The Jib and Genoa are two of the most common types.

Different types of sails are used for various sail plans and situations, and you can learn more about them in this guide .

Now that we had a look at the main parts of the boat, let us dive deeper and look at the rest of the vessel.

The starboard and port side of the boat

Learning about the boat’s components is very important, but we must also know how to orient ourselves on the vessel. Using the words “left and right” on onboard often leads to confusion.

If you refer to something on the left side of the boat, the person facing you will be confused. He won’t know if you are referring to his or your left. This is where the terms “Port” and “ Starboard ” make better sense.

When facing the front of the boat or the bow , your left side of the boat is the port side, and the right-hand side is the starboard . If you turn around and face the back of the boat or the stern , your right-hand side will be the port side.

- A red light identifies the port side of a vessel.

- A green light identifies the starboard side of a vessel.

Windward and Leeward

- The windward side of the boat is the side facing the wind. If the wind comes from your right-hand side while facing forward, the starboard side is windward. This will be the boat’s high side as the wind heels the boat over.

- The leeward side of the boat is the side opposite to the wind. This will be the lower side of the ship while sailing as the wind heels the boat over.

Windward and leeward are two of the most important aspects to understand when sailing and navigating. Not only to identify equipment and gear on each side of the boat but to avoid collisions when sailing close to other vessels. There are rules on the water dictating which boat is “Stand On” and which has to “Give Way” depending on whether you are the windward or the leeward vessel in the situation.

Read this article to access a free course on navigation rules .

Basic parts of a sailboat

The boat’s bow is the front part, typically shaped like a “V” to cut through the waves. Larger vessels often have a locker for their anchor chain in this section, holding the anchor at the front.

The midship section is the center of the boat. Some refer to this part as amidships.

The stern is the rear or back part of the boat. It is also referred to as the aft . I’ve had French crew calling the stern the butt of the vessel, which is funny but also correct!

The beam is the widest part of the boat. Also referred to as the sides on the middle.

The transom is a flat surface across the stern of the boat.

The waterline is the part where the hull (body) of the boat meets the water. Many vessels have a painted stripe to mark the waterline, indicating how loaded the ship is. If you have too much stuff on board, the waterline goes underwater, and it is time to do some housekeeping!

The freeboard is the vertical part of the ship side between the water and the deck. When you see a blue boat like Ellidah, the freeboard is the blue part.

The deck is the “floor” of the boat when you are outside. You have probably heard the term “All hands on deck!” The front deck is the deck space in front of the mast. Side decks are the decks on the boat’s sides.

The mid-deck is between the cockpit and the mast. The aft deck is the deck behind the cockpit. Sailboats with aft cockpits often don’t have any aft decks, but some have a swimming platform instead.

The cockpit is the boat’s steering position and where you will find the helm.

The helm is the position the helmsman uses to steer the boat. Smaller sailboats often use a tiller to navigate, while most bigger yachts have one or two steering wheels.

Main parts below deck (inside the boat)

Let us look at the interior to highlight and learn about the parts we have below the deck.

The Companionway

The companionway is the “front door” of the boat. This is where the steps lead from the cockpit or deck down below. It is usually opened and closed using a hatch, two doors, or a plate.

The Galley

The galley is the boat’s kitchen. This is where sailors prepare their delicious meals.

The Saloon

The saloon is basically the boat’s living room, usually where you find the settee and dinette. This is where delicious meals from the galley are served together with refreshing beverages in good company.

The settee is the sofa or couch in a boat. It is also used as a sea berth to sleep in when sailing.

The dinette is the area where you can sit down at a table and eat your dinner. It’s also perfect for consuming rum and a game of cards in good company.

A cabin is often used as a bedroom in a boat but is not necessarily where you sleep. Many boats have more than one cabin.

A berth is a place in the boat where you can sleep. This doesn’t necessarily have to be a bed and can often include the sleeping space in the saloon. Sea-berth usually refers to a sleeping position where you are tucked well in and can sleep when the boat is heeling over and moving around.

The head is the toilet on a boat. If your skipper tells you to go and clean the head, getting out the shampoo won’t do you any good!

Nav station

The navigation station is usually a chart table and a console with mysterious instruments like radios, switchboards, and complicated electronics. This is where adventures are planned and the skipper’s favorite seat onboard.

The bilge is a space in the bottom of the hull where water collects and sometimes a storage space for all sorts of things. It usually contains a bilge pump to pump out water that finds its way into the boat in various places.

A v-berth is a bed in the front cabin shaped like a V.

A bulkhead is a wall inside the boat, usually supporting the structure.

Hardware and Equipment

Sailboats come equipped with a variety of different hardware and equipment. While the specific items may vary from boat to boat, there are some essentials that nearly every sailboat has.

A winch is a metal drum that gives you a mechanical advantage and is used to control and tighten lines. These can be operated by turning a line around it and pulling manually or by a winch handle to get more force.

Most modern winches are so-called “self-tailing,” which means they lock the line on so you can winch the line without holding on to it. Some boats even have electrical winches operated by a button.

A cleat is a fitting used to fasten a rope. Most boats have at least 6 of these. One on each side on the bow, midship and stern. These are used to secure the boat to a mooring buoy or key. Many ships have more cleats than this for various lines and ropes, and they can be used for anything as they are strong points fitted to the hull.

The sprayhood is the boat’s windshield that protects the people in the cockpit from sea spray. Some vessels have a canvas sprayhood that can be folded down or removed. Others have solid sprayhoods, often called a hard dodger or a doghouse .

The bimini is the cockpit’s “roof.” It protects you from the elements and shelters you from spray, rain, and burning sun rays! A bimini can be made of canvas or hard material. A hard bimini can also be called a hardtop .

Dinghy

A dinghy is a little boat you use to get from the mothership to shore when you are at anchor, also called a tender or annex . It can be everything from a small inflatable rubber kayak to a RIB or even a solid boat.

An essential and valuable piece of kit as it is the daily driver for most cruisers. It is like the car of a land crab, used for all commuting on the water and hauling important stuff like beer, rum, and food onboard. Dinghies often have electric or petrol engines, which we call outboards.

Dinghies are also great to use for watersports, such as wakeboarding!

Like Captain Ron said in the movie, fenders are the rubber bumper things you hang off your boat to prevent it from scratching against something like the pontoon or another ship. It is conveniently also used to sit on or as a backrest while relaxing on deck.

A boat hook is a long stick with a hook at the end. Used to grab lines, items, and stuff that is too far to reach by hand, like cushions flying overboard. It is also convenient as a tool to push the boat away from another craft or the key. Most vessels have them on board.

The guard rail can be a flexible wire or a solid metal rail surrounding the boat to prevent us from falling overboard. Some also use a net as an addition for increased safety.

The pushpit is a metal guard rail around the stern of the boat. This is where the guard rail is secured on the stern: a common place to mount the BBQ, life raft, and the outboard for the dinghy.

The pulpit is the metal guardrail on the bow. This is where the guard rail is secured onto the bow.

The stanchions are the metal bars that keep the guard rail in place around the boat between the pushpit and the pulpit.

An arch is a typical structure made of stainless steel on the back of a boat and is often used to mount a variety of items like antennas, radars, solar panels, wind generators, etc. It is also convenient to use for lifting the dinghy and its outboard.

Ground Tackle

The ground tackle consists of several things:

- Your anchor

- Your anchor chain

- The link between the two

- The connection between the chain and your boat

It includes all equipment holding your boat to the ground. Larger boats sometimes have two anchors on the bow.

A windlass is a winch that hoists and lowers the anchor and chain. Most boats have one on the bow and some on the stern. These incredible things can be electrical or manual (some are both) and are essential to anchor your boat when not in a port or marina.

VHF stands for “Very High-Frequency Radio.” It broadcasts on the VHF network and allows you to communicate with others around you. Sadly, you won’t be able to tune in to your favorite radio show on these.

Still, they are essential for contacting other boats and port authorities. It is also the radio you will transmit an emergency mayday over in case of emergency. VHF radios sometimes require a license, depending on the country you are in.

Chartplotter

A Chartplotter is a navigation computer that shows various information on a screen, like charts, routes, radar images, etc. It is another vital piece of equipment that helps you navigate and maneuver the boat.

Final words

I hope this guide has been helpful and not too overwhelming for you. We’ve covered many of the parts of a sailboat and its terms and functions, but this article only touches on the basics. If you want to keep learning about sailing, I have written several other guides to help you get started.

Now that you have a basic understanding of sailboats, it’s time to take the next step and dive into a sailboat’s standing rigging .

Sharing is caring!

Skipper, Electrician and ROV Pilot

Robin is the founder and owner of Sailing Ellidah and has been living on his sailboat since 2019. He is currently on a journey to sail around the world and is passionate about writing his story and helpful content to inspire others who share his interest in sailing.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Parts of a Sailboat

Sailboats share many parts with other boats, such as keels, decks, and sometimes engines. But parts like halyards, sheets, and blocks are unique to sailboats.

Sailboats require four main parts to operate: a hull, mast, sail, and rudder. The hull is the body of the boat, and all other parts are directly or indirectly connected to it. The mast is a long pole that serves as a guide and mounting point for the sail. The sail catches the wind and propels the boat, and the rudder directs the boat and acts as its steering.

Here are all the main parts of a typical cruising sailboat , including hardware, lines, controls, cabin items, and a rundown of common sailing terminology.

Table of contents

Port, Starboard, Bow, Stem, and Stern

Before we get into the parts of a sailboat, let’s get a handle on sailboat direction. The bow of the boat is the front (forward), and the stern is the rear (aft). The stem is the forward-most part of the bow and determines its shape. These words describe the general area of front and back.

When determining port and starboard, picture looking down on the boat with the bow oriented forward. The port side is the left side of the boat, and the starboard is the right side. Now picture yourself at the controls of your boat.

If your lookout sees an obstacle off the port bow, which direction should you look? That’s right—the obstacle is forward and to the left of you. Now, we’ll go over the basic parts of a sailboat.

Basic Parts of a Sailboat

What are the basic parts of a sailboat? These are items that are essential to the operation of the boat and universal across most sailing craft. Every sailor should know where these parts are and what they do. Here are nine fundamental sailboat parts, their function, and why they’re important.

The hull is the ‘boat’ itself. It comprises the frame of the boat, the skin that keeps the water out and serves as the mounting point for everything else on the boat (both directly and indirectly). Simply put, if you punch a hole in the hull, water will come into the boat. Sailboat hulls are constructed most commonly out of fiberglass or hardwood (such as white oak), but some boat hulls are made out of aluminum, steel, and even a material called ferrocement.

The deck is the platform that covers the hull. It’s the place where you walk when you’re not inside the boat. Most people would consider the deck as any place ‘on top’ of the hull. The deck serves as a mounting point for essential boat hardware such as the mast and winches. We’ll get into those later; just think of the deck as the visible top area of the vessel. Decks are often made of fiberglass as well, but traditional boats use teak wood planking in this area. You’ll often find abrasive anti-slip material on the deck, as sailors often walk across it in wet conditions.

The keel is the structural backbone of the boat. It’s located in the bottom of the hull and serves as a sort of ‘spine’ to which all frame members are mounted during construction. The keel is an essential part of the boat and cannot be broken or damaged. You’ll often hear the term ‘keelboat’ in the sailing community. This word describes a sailboat with a long and deep keel, which is like a thin fin that runs the length of the hull. Keelboats are seaworthy vessels, as the elongated hull adds stability and keeps the boat on a straight track.

Centerboard

Many sailboats don’t have a long, deep keel, but they still need some sort of fin to keep the boat tracking straight. To substitute a long keel, many boats utilize a dagger-like board called a centerboard . This plate protrudes underneath the center of the boat, usually between one and three feet below the bottom of the hull. Centerboards are often retractable, which is great for towing and beaching. Centerboards are most common on small sailboats designed for inland or coastal cruising.

The cockpit is usually located in the rear of the boat. It features seating for the crew and controls for the steering, sails, and engine. The cockpit is the command center of the sailboat and often features storage lockers under the seats. Many cockpits are self-draining, which means they’re located above the water line and clear themselves of water accumulation. Some sailboats have enclosed cockpits for off-shore sailing. In a typical cruising sailboat , the cockpit usually takes up ⅓ of the total length of the boat or less.