- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The Shipwreck That Led Confederate Veterans To Risk All For Union Lives

Jon Hamilton

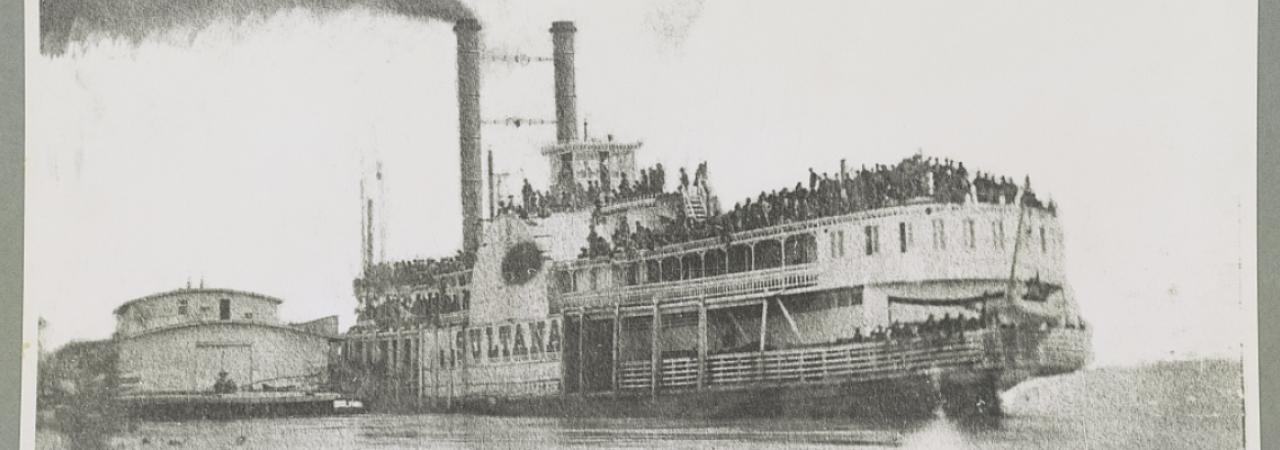

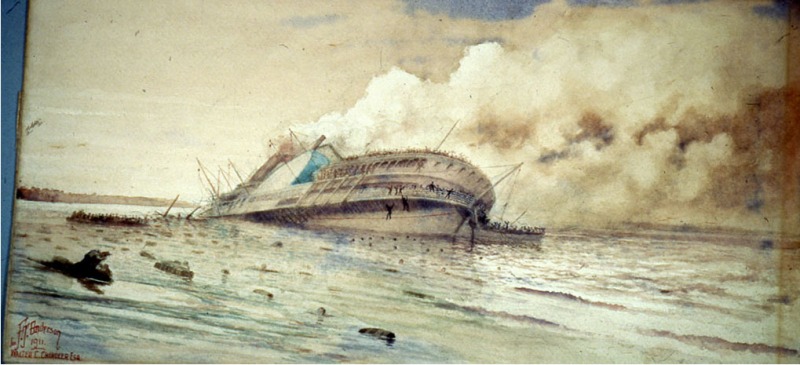

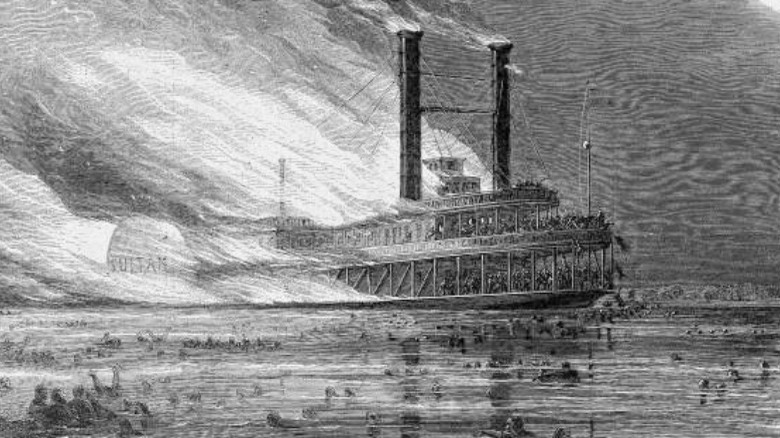

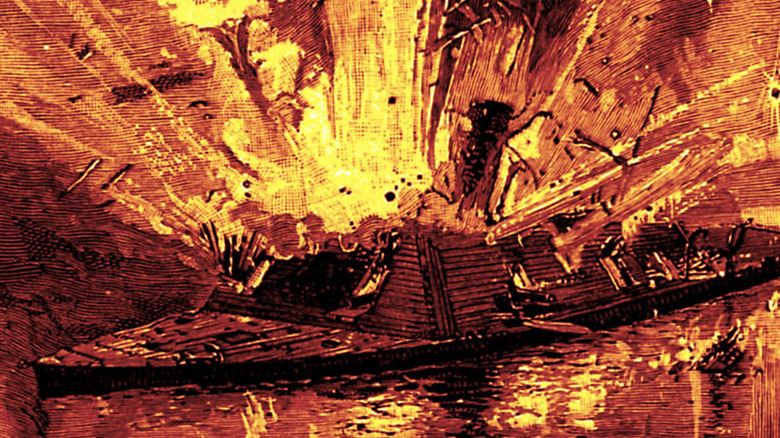

An engraving of the Sultana explosion, published in Harpers Weekly , May 20, 1865. An estimated 1,800 people died in the explosion and ensuing fire — more than died in the sinking of the Titanic . Library of Congress hide caption

An engraving of the Sultana explosion, published in Harpers Weekly , May 20, 1865. An estimated 1,800 people died in the explosion and ensuing fire — more than died in the sinking of the Titanic .

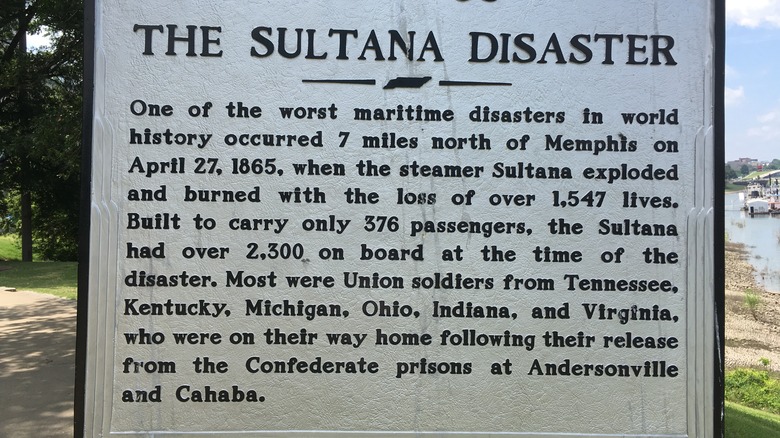

On April 27, 1865, the steamboat Sultana exploded and sank while traveling up the Mississippi River, killing an estimated 1,800 people.

Titanic: Voyage To The Past

The event remains the worst maritime disaster in U.S. history (the sinking of the Titanic killed 1,512 people). Yet few know the story of the Sultana's demise, or the ensuing rescue effort that included Confederate soldiers saving Union soldiers they might have shot just weeks earlier.

So on the 150th anniversary of the sinking, the city of Marion, Ark., is trying to make sure the Sultana will be remembered. The city has created a museum and is hosting events intended to bring attention to the tragedy.

Marion, across the river from Memphis, Tenn., is near the spot where the 260-foot side-wheeler came to rest. "We feel like we're a part of this Civil War story, but we're the conclusion that no one heard," says Lisa O'Neal, a Marion resident and member of the Sultana Historic Preservation Society.

The Sultana was on its way from Vicksburg, Miss., to St. Louis when the explosion occurred, says Jerry Potter, a Memphis lawyer and author of The Sultana Tragedy. It was just weeks after the Civil War ended, Potter explains, and the vessel was packed with Union soldiers who'd been released from Confederate prison camps.

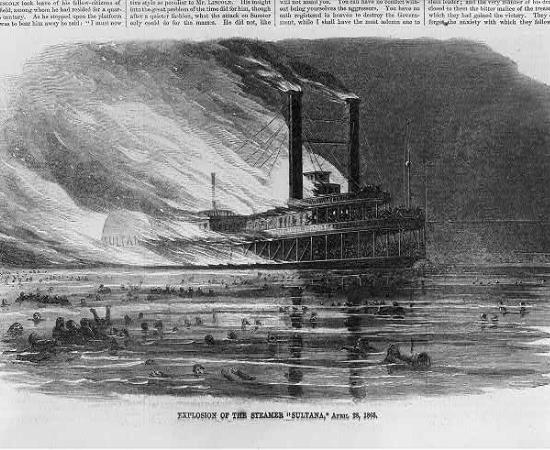

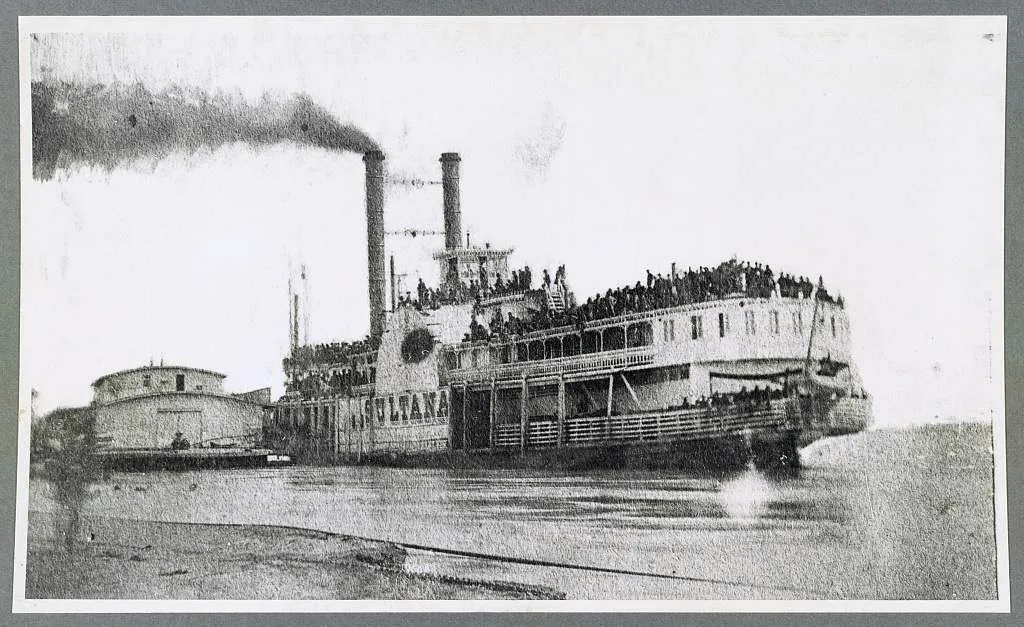

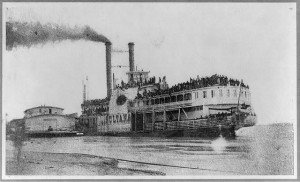

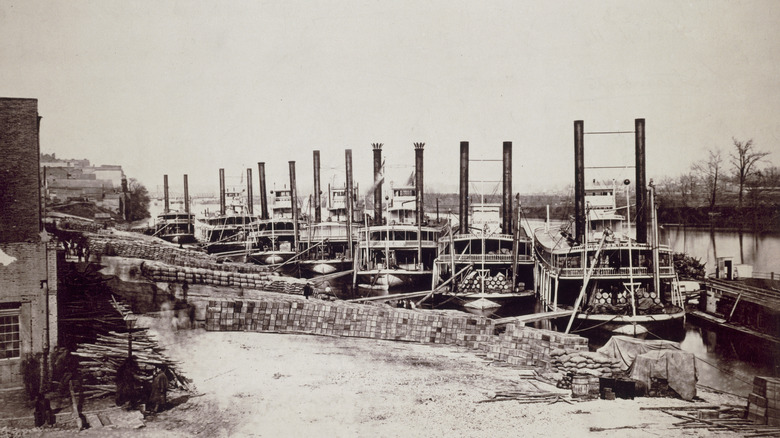

The ill-fated Sultana in Helena, Ark., just before it exploded on April 27, 1865, with about 2,500 people aboard. Most were Union soldiers, newly released from Confederate prison camps. Library of Congress hide caption

The ill-fated Sultana in Helena, Ark., just before it exploded on April 27, 1865, with about 2,500 people aboard. Most were Union soldiers, newly released from Confederate prison camps.

"The boat had a legal carrying capacity of 376 passengers," he says, "and on its up-river trip it had over 2,500 aboard," in part because the government had agreed to pay $5 for each enlisted man and $10 for each officer who made the trip.

Today, Potter describes the scene from a park along the banks of the Mississippi, just north of Memphis. "The river is at flood stage," he says as we watch a barge struggle to move up river, "very similar to what it was on April 27, 1865." That day, he says, the water was moving very quickly and contained a lot of trees and other debris. And it was very cold.

The Sultana made it only a few miles north of Memphis.

"At 2 a.m., one of the boilers exploded, resulting in two other boilers exploding," Potter says. "And the entire center of the boat erupted like a volcano."

Soldiers from Kentucky and Tennessee were among the first to die, he says, "because they'd been packed in next to the boilers.

"It was like a tremendous bomb going off in the middle of where these men were," Potter says. "And the shrapnel, the steam and the boiling water killed hundreds."

Fire, drowning and exposure would kill many hundreds more. But the story of the Sultana is about more than lost lives. It is also about a rescue effort that brought together people who had been at war just weeks earlier.

Many Sultana survivors ended up on the Arkansas side of the river, which was under Confederate control during the war. And many of them were saved by local residents, like John Fogelman — an ancestor of the city of Marion's current mayor, Frank Fogelman.

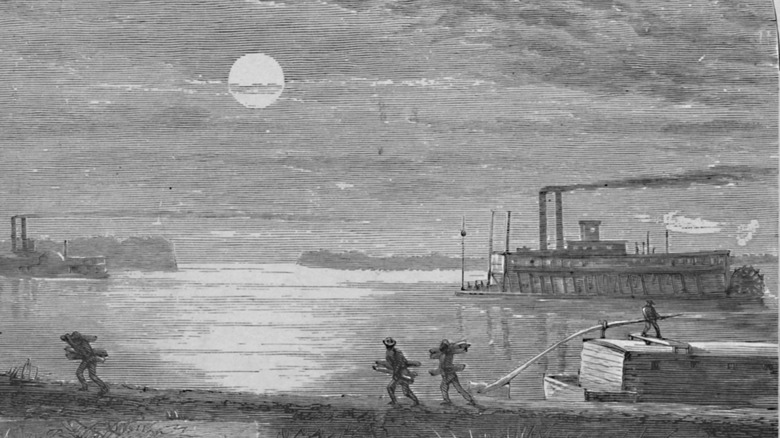

Newspaper accounts suggest John Fogelman and his sons spotted the burning Sultana as the remains of the paddle-wheeler drifted downriver.

"The wind blew the fire to the rear, burned that out," Frank Fogelman says. "The paddle wheel fell off of one side, caused the boat to turn sideways; the other paddle wheel fell off."

Eventually the Sultana turned so that the wind was pushing the flames toward the bow, where 25 soldiers remained. Fogelman's ancestors didn't have any boats to reach the trapped soldiers, so they improvised.

"I understand that the Fogelmans were able to put together some logs to make a raft and go out and take people off the boat as it drifted back this way," Fogelman says. "In order to save time, they would set the people off in treetops, and go back to the boat to take more off."

All 25 soldiers were rescued, historians say, and the Fogelman home became a refuge for Sultana survivors.

Passing boats and bystanders on both sides of the Mississippi helped pull survivors from the muddy water. But some of the most poignant stories involve Confederate soldiers rescuing their Union counterparts.

Frank Barton is the descendant of one of those Confederate soldiers, a man named Franklin Hardin Barton.

"He served in the 23rd Arkansas Cavalry, and he was tasked with, among other things, raiding ships going up and down the river," Frank Barton says. "A few weeks earlier, he might have been attacking the Sultana if it had come in."

Instead, newspaper accounts say Franklin Barton saved several Union soldiers.

The story of the Sultana isn't well-known even among people who live along the Mississippi. Potter, the lawyer and author, grew up around Memphis, but didn't learn about the tragedy until the late 1970s, when he saw a painting of the ship in flames.

Discovery Gives New Ending To A Death At The Civil War's Close

Potter says he went to the library to learn more and wondered, "Why haven't I ever heard of this?" Since then, he says, studying the Sultana has become an obsession.

Who Was John Wilkes Booth Before He Became Lincoln's Assassin?

As a lawyer, Potter was well-equipped to investigate the mistakes and malfeasance that led to the Sultana disaster. In his book, he builds a strong case against the boat's captain and co-owner, J. Cass Mason.

"It's clear that he had bribed an officer at Vicksburg to ensure that he would get a large load of prisoners," Potter says.

The Sultana's captain and its chief engineer also allowed a mechanic to make a quick and inadequate repair to a damaged boiler, Potter says. "He told the captain and the chief engineer the boiler was not safe, but the engineer said he would have a complete repair job done when the boat made it to St. Louis."

Evidence like that may have led the government to downplay the Sultana tragedy, Potter says. But there were many other reasons the event didn't get much attention at the time.

"The war had just ended a few weeks before," he says. "Lincoln had just been assassinated. And the boat was filled with enlisted men primarily — men who really hadn't made a mark in history or a mark in life." But perhaps the best explanation is that after years of bloody conflict, the nation was simply tired of hearing about war and death.

Today, though, the city of Marion, Ark., thinks people are ready to learn about the Sultana. The temporary museum it has created near City Hall includes pictures, personal items from soldiers, pieces of the Sultana , and a 14-foot replica of the boat.

But what the museum really has to offer is a powerful story of soldiers who died just days away from seeing their families and loved ones.

"They had survived war," O'Neal says. "They had survived prison in one of the most hideous places the South had. It just hurts my heart."

- Mississippi River

- 601.576.6936

Surviving the Worst: The Wreck of the Sultana at the End of the American Civil War

Theme and time period.

It was late April 1865 and more than 2,000 tired, sick, and injured men, wearing dirty and tattered clothes, filed down the bluff from Vicksburg to a steamboat waiting at the docks on the Mississippi River.

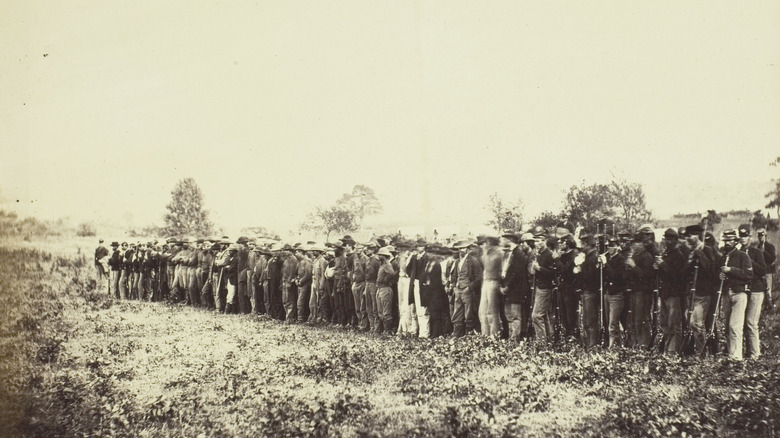

The city of Vicksburg was ravaged by the American Civil War, and so were the men who were about to board the steamboat Sultana . Almost all were Union soldiers who had survived the battlefields only to be captured by Confederate troops and sent to prison camps in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi.

Most of the soldiers were young, including some who were only 14 years old. Boys could enlist, usually as musicians, with their parents’ permission, but some enlisted as soldiers by lying about their age. Many of the soldiers had already been injured in battle by the time they reached the prison camps, and their situation soon got much worse.

Prison camps

The Confederate prison camps were dirty, disease-ridden places and food and medicine were in short supply. This was true of prison camps on both sides, but life in the southern camps got considerably worse toward the end of the war when the Confederacy was having trouble feeding and caring for its own soldiers and citizens. Thousands of men died in the prison camps of starvation and disease. At the Alabama camp at Cahaba, the Alabama River jumped its banks and the flood forced the men to stand in waist-deep water for a week in winter.

By the spring of 1865, however, the war was close to its end, and the opposing armies agreed that it was time to release their prisoners and send them home. This was the best news the prisoners could hear. Soon they would be back home, close to their loved ones, with plenty to eat and a bed of their own to sleep in – everything they had dreamed of during their military service and captivity.

After the prisoners were released they had a hard time making their way west across the South to Vicksburg, where, they had been told, steamboats would carry them to their homes in the north. Traveling north from Vicksburg on the Mississippi River, boats could reach the Missouri, Ohio, and Tennessee rivers and, from there, the towns of the American Midwest from which the soldiers had come. But to get to the Mississippi River at Vicksburg the soldiers had to travel by boat, by train, and on foot. Because they were so weak from their war and prison experiences some of them died along the way. Making matters worse, some of the trains derailed due to the damaged railroad tracks — many of the railroad tracks had been destroyed by the war. In 1865 there were no highways and not even many good roads.

Rivers were then the best way to travel; they were like the interstate highways of the 21st century. After the recently freed prisoners reached Jackson, Mississippi, they had to walk the rest of the way to Vicksburg, which was then about 50 miles on the old road. Many of the men had no shoes and their feet were bleeding by the time they reached the Big Black River, just east of Vicksburg. They were also extremely hungry.

The Big Black River marked the dividing line between the part of Mississippi held by the Union army (which included Vicksburg) and the part held by the Confederate army (which included the area closer to Jackson). By then the fighting had ended, but only after they reached the area held by the Union army were the recently freed prisoners truly free. There, after crossing the Big Black River, they were given clean clothes and food at Camp Fisk, a neutral holding pen for prisoners of war. While arrangements were being made to transport them north on the Mississippi River they stayed in the camps outside Vicksburg, without tents or even blankets, and many got sick while waiting to board a steamer.

One reason for the boarding delay was that the owners of the steamboats were competing to see who could arrange for the most freed prisoners on their boats. The steamboat companies were paid as much as $10 per person to transport soldiers and freed prisoners, which was a lot of money in 1865, and some of the company employees bribed army officials in Vicksburg to make sure they got as many passengers as possible.

The steamship Sultana

The Sultana was 260 feet long and 42 feet at its widest point and was designed to carry about 375 passengers and crew. It already had about 180 private passengers and crew on board, but by the time more than 2,000 paroled prisoners, their Union Army guards, a few Confederate soldiers headed home, and members of the U. S. Sanitary Commission boarded, the boat left Vicksburg with about 2,400 people on board – more than six times its capacity. There was standing room only. Many of the freed prisoners were so sick or badly injured that they had to be carried aboard. Still, the men were glad because they were on their way home.

Unfortunately, the worst was still ahead. The overcrowded Sultana left Vicksburg traveling upriver to Memphis, Tennessee. Because the snow had melted in the north, the river was flooded and the boat struggled against the currents with its heavy load. In Memphis the boat docked and some of the men got off and toured the town. Late that night they re-boarded the boat and headed upriver again. Around 2 a.m., while most of the men were sleeping, the Sultana exploded and caught fire about seven miles upriver from Memphis. Some people later claimed the Sultana had been sabotaged by Confederate soldiers, but the United States government concluded that the boilers that heated water for its steam engines had exploded due to a faulty design and the heavy load of its human cargo.

Fires built in enclosed chambers heated water to the point that it turned to steam, and the pressure of the steam turned turbines that propelled water wheels, which in turn propelled the boat. A leak in the tubes that carried the super-heated water caused the explosion of the Sultana’s boilers, which destroyed the nearby parts of the boat and sent hot water and burning embers onto the sleeping passengers. Some were killed instantly by the explosion. Others awoke to find themselves flying through the air, and did not know what had happened. One minute they were sleeping and the next they found themselves struggling to swim in the very cold Mississippi River. Some passengers burned on the boat. The fortunate ones clung to debris in the river, or to horses and mules that had escaped the boat, hoping to make it to shore, which they could not see because it was dark and the flooded river was at that point almost five miles wide.

Of the approximately 2,400 people on board, about 1,700 died. The Sultana remains the worst maritime disaster in American history — more people died than with the 1912 sinking of the Titanic . There are reasons why the Sultana disaster is not well-known. The Civil War had just ended and President Abraham Lincoln had been assassinated, and the day before the Sultana disaster, Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, had been killed. Also, the American public had grown accustomed to hearing about loss of life on a large scale as a result of the battles of the war. A steamboat disaster was not enough to make big news. The Sultana disaster is rarely mentioned in history books.

Most of the passengers who survived did so by floating on pieces of the boat until they made it to shore or could be rescued. One man survived by floating almost 10 miles on the back of a dead mule. One survivor recalled that there was at least one person clinging to every tree along the flooded banks of the river. All of them were very cold, and some sang songs to try to keep their mind off their troubles. Other survivors mimicked the sounds of birds or frogs.

Word of the disaster reached Memphis when a passenger, a teenage boy, floated up to the waterfront and told the sentries what had happened. In the early morning hours of April 27, 1865, as word of the disaster spread, numerous boats began to assist in the rescue, and the survivors were sent to hospitals in Memphis. Many were naked by the time they were rescued, having shed their clothes to make it easier to swim. In Memphis they were given red long johns (much like thermal long underwear), which some of them wore as they wandered the streets of Memphis.

When they were well enough, the survivors were put on other boats and sent north, where they finally made it home. The Sultana remained at the bottom of the Mississippi River.

Alan Huffman is the author of Sultana: Surviving the Civil War, Prison and the Worst Maritime Disaster in American History. New York: Smithsonian Books, 2009 .

Lesson Plan

- Surviving the Worst: The Wreck of the Sultana at the End of the American Civil War Lesson Plan

Selected bibliography

Berry, Chester D., ed. Loss of the Sultana and Reminiscences of Survivors . 1892. Reprint, Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 2005.

Bryant, William O. Cahaba Prison and the Sultana Disaster . Tuscaloosa, Ala.: University of Alabama Press, 1990.

Elliott, James W. Transport to Disaster . New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1962.

Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative . New York: Random House, 1963.

Potter, Jerry O. The Sultana Tragedy: America’s Greatest Maritime Disaster . Gretna, La.: Pelican Publishing Co., 1992.

Salecker, Gene Eric. Disaster on the Mississippi: The Sultana Explosion, April 27, 1865 . Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1996.

Speer, Lonnie R. Portals to Hell: Military Prisons of the Civil War . Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books, 1997. Reprint, Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebreska Press, 2005.

Help us bring Mississippi's history to the classroom. Become a member of the Mississippi Historical Society now.

Join the mississippi historical society.

The Sultana Disaster

In the early hours of April 27, 1865, mere days after the end of the Civil War, the Sultana burst into flames along the Mississippi River. The Sultana was a 260-foot-long wooden steamboat, built in Cincinnati in 1863, which regularly transported passengers and freight between St. Louis and New Orleans on the Mississippi River.

On April 23, 1865, the vessel docked in Vicksburg to address issues with the boiler during a routine journey from New Orleans. While in port, it was contracted by the U.S. Government to carry former Union prisoners of war from Confederate prisons, such as Andersonville and Cahaba, back into Northern territory. In order to fulfill the lucrative contract, J. Cass Mason, the Sultana ’s captain, opted to patch the leaky boiler rather than complete more extensive and time-consuming repairs. Fearing that his colleagues were taking bribes to transport prisoners on other boats, Union Army Captain George Williams, who oversaw the operation, hastily ordered that all former prisoners at the parole camp and hospital at Vicksburg be transported on the Sultana . Although it was designed to only hold 376 persons, more than 2,000 Union troops were crowded onto the steamboat - more than five times its legal carrying capacity. Despite concerns of overloading from several officers, Williams refused to divide the men, insisting that they travel on one vessel.

The Sultana steamed north up the Mississippi, but the severe overcrowding and faster river current caused by the spring thaw put increased pressure on its newly patched boilers. Shortly after leaving Memphis, Tennessee on April 27th, the overstrained boilers exploded, blowing apart the center of the boat and starting an uncontrollable fire. Many of those who were not killed immediately perished as they tried to swim to shore. Of the initial survivors, 200 later died from burns sustained during the incident. Researchers indicate that 1,195 of the 2,200 passengers and crew died, making the Sultana incident the deadliest maritime disaster in U.S. history.

Impressment

Charleston during the Civil War

Charleston Harbor

Explore civil war navies.

- Skip to main navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

As Much as the Water: How Steamboats Shaped Arkansas

Center for Arkansas History and Culture

Understanding the Sultana Tragedy: The Long Way Home

On April 24, 1865, a steamboat named Sultana left Vicksburg, Mississippi, bound for Cairo, Illinois. On board were 2,300 Union soldiers who had just been released from southern prisons during the Civil War. These soldiers were in poor physical health due to the conditions they suffered in the prisons. Many were malnourished and too sick to eat. Some had gone from weighing almost 200 pounds to weighing less than 100 pounds. The Sultana also carried 100 civilian passengers and a crew of 85. The ship was designed to legally hold 376 passengers.

The decks were so crowded that you couldn't walk on them without stepping on soldiers as they lay side by side on the decks. As the ship was loaded, the hurricane deck began to sag and had to be reinforced. In addition to the large number of passengers, the ship was also carrying 250 hogsheads of sugar, about 100 mules and horses, and 100 hogs. If these conditions weren't bad enough, the Sultana also had a boiler that needed to be repaired. The captain of the ship, J. Cass Mason, didn't want to wait, so he had the boiler patched and left Vicksburg with his overloaded ship.

The ship traveled upriver arriving at Helena, Arkansas, where a photographer ran out to snap a picture of the overcrowded boat (as shown in attachment ). When the soldiers saw the photographer, they all ran to the side of the ship to be in the picture. When they did, the ship began to tilt to that side. The captain began shouting for them to get back to their places before they overturned the ship and caused it to sink.

The Sultana left Helena and reached Memphis around 6:30 p.m. on April 26, 1865. Here it unloaded the sugar and many of the soldiers went into town to find food, as there wasn't enough onboard the ship and not enough cooking facilities for what food was available. The ship left Memphis around 11:00 p.m. and stopped at Hopefield, Arkansas, to load coal to power the boilers.

Then approximately seven miles north of Memphis, around 2:00 a.m. on April 27, the Sultana's boilers exploded, sending soldiers flying into the dark waters of the Mississippi River. Many of the soldiers were killed instantly and others scrambled over the side of the ship as they realized it was on fire. Hundreds jumped together and drowned as they pulled each other down. Others on the ship grabbed boards and other objects to try and float down the river. Some even clung to the mules and horses as they went down the river. The night was very dark and the river was flooded; it was almost four miles wide. This prevented the passengers from being able to find the shore. As they were in such poor condition, most did not have the strength to fight the river, other passengers clinging to them, and the cold water.

When morning arrived, ships at Memphis discovered what had happened and began searching for survivors. Of the almost 2,500 people aboard the Sultana , only 757 were rescued and of that almost 300 died in the hospital. This disaster claimed more lives than the Titanic , yet never received the attention. It was overshadowed by President Abraham Lincoln's death on April 14, 1865.

There was only one person ever charged with the overloading of the Sultana , Captain Frederick Speed. He was found guilty, but was later exonerated of all charges by the judge advocate general. Today, there is still no national monument to honor these men who fought for our country, suffered through the inhumane conditions of southern prisons, were packed onto a ship like animals, and lost their lives on their journey home, yet it remains the worst maritime disaster in American history.

Neither William H. Norton's poem nor this summary of the disaster even begins to describe the horrors seen and heard that April night in 1865. It doesn't tell of the struggle the men faced in returning to civilian life, or of their fight to have their tragedy remembered. It doesn't tell of the nightmares, images, and sounds that would plague the men for the rest of their lives.

About the Author

Brandie L. Mikesell is an Archivist for the Center for Arkansas History and Culture.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

This Day In History : April 27

Changing the day will navigate the page to that given day in history. You can navigate days by using left and right arrows

Sultana steamship explosion kills 1,700

The steamboat Sultana explodes on the Mississippi River near Memphis, killing 1,700 passengers including many discharged Union soldiers. The accident is still considered the largest maritime disaster in U.S. history.

The Sultana was launched from Cincinnati in 1863. The boat was 260 feet long and had an authorized capacity of 376 passengers and crew. It was soon employed to carry troops and supplies along the lower Mississippi River.

On April 25, 1865, the Sultana left New Orleans with 100 passengers. It stopped at Vicksburg, Mississippi, for repair of a leaky boiler. R. G. Taylor, the boilermaker on the ship, advised Captain J. Cass Mason that two sheets on the boiler had to be replaced, but Mason ordered Taylor to simply patch the plates until the ship reached St. Louis. Mason was part owner of the riverboat, and he and the other owners were anxious to pick up discharged Union prisoners at Vicksburg. The federal government promised to pay $5 for each enlisted man and $10 for each officer delivered to the North. Such a contract could pay huge dividends, and Mason convinced local military authorities to pick up the entire contingent despite the presence of two other steamboats at Vicksburg.

When the Sultana left Vicksburg, it carried 2,100 troops and 200 civilians, more than six times its capacity. On the evening of April 26, the ship stopped at Memphis before cruising across the river to pick up coal in Arkansas . As it steamed up the river above Memphis, a thunderous explosion tore through the boat. Metal and steam from the boilers killed hundreds, and hundreds more were thrown from the boat into the chilly waters of the river. The Mississippi was already at flood stage, and the Sultana had only one lifeboat and a few life preservers. Only 600 people survived the explosion. A board of inquiry later determined the cause to be insufficient water in the boiler–overcrowding was not listed as a cause.

Also on This Day in History April | 27

This Day in History Video: What Happened on April 27

Navigator Ferdinand Magellan killed in the Philippines

U.s. agent william eaton leads first u.s. marines battle, on “the shores of tripoli”, south africa holds first multiracial elections, universe is created, according to kepler, rocky marciano retires as world heavyweight champion.

Wake Up to This Day in History

Sign up now to learn about This Day in History straight from your inbox. Get all of today's events in just one email featuring a range of topics.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

President Ulysses S. Grant is born

Explorer zebulon pike killed in battle, d.a. announces negligence caused death of “the crow” actor brandon lee, president lincoln suspends the writ of habeas corpus during the civil war, andrew cunanan begins his killing spree, afghan president is overthrown and murdered, gm announces plans to phase out pontiac.

- Public Affairs

- The Next Chapter

- Support KET

- Membership Benefits

- Sponsorships

- More Ways to Give

- Legislative Coverage

- Estate Planning

- KET Passport

SS Sultana: The Greatest Maritime Disaster in U.S. History

Joyce West | June 14, 2016 11:27 am

In the days after the Civil War, the steamboat Sultana exploded and sank on the Mississippi River on April 27, 1865, at Memphis, killing 1,800 passengers – almost all of them former prisoners of war returning home from the South. It remains the worst maritime disaster in U.S. history.

The story of the Sultana is largely forgotten, eclipsed by the news a day earlier that President Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, had been found and killed.

Jerry O. Potter, author of “The Sultana Tragedy,” tells the tragic story of the men of the 6 th Kentucky Cavalry. “These men had survived months and years of combat, and they were captured near Tuscaloosa, Alabama, on April 1, 1865. I mean, the war was almost 10 days from being over when they were captured.”

The Sultana, a 250-foot-long steamboat built in Cincinnati in 1863, was designed to carry only 376 passengers.

Wartime transport was big business. “There was a big competition among the boats to get a load of prisoners,” Potter said. The government was paying $5 per enlisted man, $10 per officer, to carry men upriver from the South.

Potter says 1,000 men, at $5 a head, meant $5,000—a princely sum.

On April 24, 1865, three steamboats stood ready in Vicksburg, Mississippi, to take on former POWs. Most boarded the Sultana, headed for Cairo, Illinois.

“Vicksburg was a cesspool of crooked, corrupt, Union officers in 1865,” Potter said. The Sultana’s captain knew one of the four boilers was leaking and not safe, he says, yet officials ignored the danger.

Loaded with POWs, it carried close to 2,500 people on that spring day. Decks sagged under the weight of the men.

One of the clerks said that if the Sultana made it safely to Cairo, it would be the largest number of passengers ever carried upriver on a single boat.

The last known photo of the Sultana, taken as it passed through Helena, Arkansas, shows a steamboat filled shoulder-to-shoulder with men.

At 2 in the morning on April 27, 1865, the leaking boiler exploded and ignited two other boilers. “There was this tremendous explosion that completely destroyed the center of the boat,” Potter said. The Sultana was in flames.

Many of the Kentucky prisoners were placed on the boiler deck and were killed in the initial explosion. “They were so close to being home,” Potter said. “…To be virtually murdered by their own government – even after researching this for almost 35 years, I’m still horrified at what happened.”

Some soldiers, weak from their captivity, leapt overboard into the cold currents of the Mississippi. Many were unable to swim.

“No rescue efforts were really undertaken until two or three hours later when survivors started drifting…to the riverfront in Memphis,” Potter said.

Since there was no accurate record of all those aboard, identifying the number of dead proved difficult. An estimated 1,800 passengers died.

Historians say 194 Kentuckians died in the disaster. Among the dead was Union Major William Fidler of the 6th Kentucky Cavalry, the highest ranking former POW on the Sultana and the commander of the paroled POWs.

Despite the deaths, no one was held responsible. The military determined while the boat was overcrowded, it was not overloaded. “The end result is no one was punished for the worst maritime disaster in American history,” Potter said.

In fact, Potter says, the government even rejected a request from survivors to erect a monument to those who died in the tragedy.

“What would these men have become in life? A lot of them were young, never given an opportunity. To me, that’s the tragedy. That’s what we’ll never know,” Potter said.

This segment is part of Kentucky Life episode #2008 which originally aired on January 31, 2015. Watch the full episode.

Ad Blocker Detected

THE DISASTER

THE STEAMBOAT

The Sultana was a privately owned sidewheel steamboat built in Cincinnati, Ohio, in February 1863. A relatively large boat, the Sultana stood three decks tall and measured 260 feet long and approximately 70 feet wide – a little shorter than a football field and about half as wide. Built for the New Orleans cotton trade, the Sultana spent her first two years carrying troops and supplies up and down the Mississippi River for the Union Army, until Vicksburg, MS, was captured in July 1863. She then carried cotton, manufactured goods and civilian passengers between New Orleans and her home port of St. Louis, MO.

In the spring of 1864, the original owner sold the boat to a conglomerate of St. Louis businessmen including thirty-four-year-old James Cass Mason, who would captain the Sultana. Unfortunately, times were tough in the Mississippi trade, since there seemed to be more steamboats than goods. In mid-April 1865, Captain Mason set off downriver with the Sultana after making the fastest trip upriver for any steamboat at that time. In honor of his record, the Sultana was awarded a set of elk’s antlers, a symbol of a speedy steamboat, which Captain Mason immediately placed high up on the lower bracing between the twin smokestacks. Any businessman or passenger looking for a fast boat only had to look up at the coveted elk’s antlers between the stacks of the Sultana to know that Captain Mason and his two-year-old boat could deliver.

THE SURRENDER, ASSASSINATION, BRIBE AND BOILER

On April 9, General Robert E. Lee had surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant, at Appomattox, VA, marking the beginning to the end of the Civil War. On the morning of April 15, while the Sultana was sitting at Cairo, Illinois, word came over the telegraph wire that President Abraham Lincoln had been assassinated while watching a play. Knowing that telegraph communication with the South had been cut off because of the war, Captain Mason headed towards New Orleans hoping for fame as the first to boat to spread the news of Lincoln’s death.

When Captain Mason stopped at Vicksburg, MS, he was approached by Capt. Reuben Benton Hatch, the Chief Quartermaster in Vicksburg. Hatch, knowing that Mason was hurting for money because of a lack of commerce, had an offer for Mason. Almost 5,000 recently paroled Union soldiers, who had just recently been held captive by the Confederates in rebel prisons at Andersonville, GA, and Cahaba, AL, were being released to be sent home. Steamboats were taking the men home and the US Government was paying so much per man, per hundred miles, to carry them home. Hatch proposed to Mason that he could guarantee that the Sultana got at least 1,000 men (worth about $2,500, or more than $40,000 today) if Captain Mason would give him a kickback. Even though both men knew that the legal carrying capacity of the Sultana was just 376 passengers and 80-85 crew, Mason agreed to the bribe. He then continued downriver spreading the news of the assassination before coming back to get the Union soldiers.

On April 23, 1865, the Sultana limped back into Vicksburg from downriver. She had sprung a leak in one of her four boilers, and it needed to be repaired. While the work was being done to fix the boiler, the recently released soldiers began showing up. Instead of 1,000 soldiers, as Captain Hatch had suggested, the Sultana got almost 2,000 men. They were crowded together in every nook and cranny of the steamboat, as Captains Mason and Hatch knew more men meant more money. Very late in the evening of April 24, 1865, the Sultana finally backed away from the Vicksburg wharf and started upriver on her final journey. She carried on board a total of 2,137 people; 1,960 ex-prisoners, 22 guards, 85 crew members, and 70 paying passengers.

THE EXPLOSION

The overcrowded Sultana moved steadily upriver against a strong spring flood current. On several occasions, as the Sultana steamed past a southbound steamboat or passed a small farm, the men crowded to one side to wave and holler. Fearful that his boat would capsize from the sudden shift in weight, Captain Mason implored the men to stay in place. Equally as disconcerting was the fact that the sudden shift in weight caused the water inside the four inter-connected boilers to slosh back and forth, decreasing water in the highest boiler and increasing the level of water in lowest boiler. The highest boiler, without water, would still be exposed to the fire from the furnaces and would become red hot. When the Sultana shifted back to an even keel, the water would return to the super-heated boiler and turn to instant steam. With the Sultana’s boilers already taxed against the spring flood, a sudden increase in pressure would be dangerous.

On the morning of April 26, 1865, Sultana stopped at Helena, Arkansas where photographer Thomas W. Bankes captured an image of the overcrowded steamboat (see photo). Near 7:00 p.m. the Sultana reached Memphis, where about 300,000 pounds of sugar was removed from the hold. The top-heavy vessel, which had tilted quite often despite the extra weight down in the hold, would tilt even more now. Near 1:00 a.m. on April 27, after unloading the sugar and taking on a new load of coal, the Sultana finally started on the last leg of the journey towards Cairo, Illinois, where the men were to be transferred to trains and taken to Camp Chase, near Columbus, Ohio for mustering out.

Around 2:00 a.m., when the Sultana was about seven miles north of Memphis, three of the four boilers suddenly exploded. The horrendous explosion came from the upper back part of the boilers and ripped upward through the heart of the Sultana. The blast went up at about a 45-degree angle, ripping apart the center of the main cabin, destroying the middle of the texas cabin (the section of a steamboat that includes the crew's quarters), and shearing off the back two-thirds of the pilothouse.

Since the explosion had not come from the furnace fireboxes, the Sultana did not burst into flames immediately. With the loss of three of the four huge boilers, the towering smokestacks lost their support and toppled. The right smokestack fell into the giant hole in the center of the Sultana while the left stack crashed heavily onto the center of the crowded hurricane deck, smashing it down onto the equally crowded second deck underneath. Dozens and dozens of soldiers were crushed to death between the two decks although some were saved by the support of the heavy railings outlining the openings of the main stairway.

As the debris from the wrecked upped decks slid down into the exposed fireboxes, the center of the Sultana slowly burst into flames. A few soldiers tried to put out the flames but they could not locate any of the fire buckets. The men had used them to retrieve water from the swollen Mississippi and had not returned them to their racks. It was not long before the entire middle of the steamboat was in flames.

Many people had been catapulted into the river by the force of the explosion while hundreds more fought to get away from the spreading flames and to find scraps of lumber to keep them afloat in the water. People trapped in the wreckage cried out for assistance as men women, and children who were lucky enough jumped into the icy cold river. Many of the ex-prisoners, emaciated from their time in Southern prisons, soon lost their strength and grabbed onto anything that might help them stay afloat – a scrap of wood, a swimming horse, another struggling human being.

At first, the bow of the Sultana was facing into the wind and the flames were blown only backward towards the stern. Many people on the bow stopped their panic and waited while the people behind the flames leaped into the water and fought to survive. Eventually, however, one of the big side paddlewheel boxes broke away and fell into the water causing the steamboat to turn completely around. By the time the second paddle wheel box broke away and fell into the river, stabilizing the vessel, the bow was pointed downstream and the flames were suddenly being pushed back towards the bow. All of those who had sought safety on the bow while flames were blowing toward the rear, were now suddenly in the path of the advancing flames.

Approximately four hundred men and a few women had clustered on the bow when the flames began blowing their way, and by now most of the floating debris was gone, taken by the first group to leave the boat. Pushing and shoving into the water, men and women grabbed onto each other as they fought a life-or-death battle to keep their heads above the freezing, swirling waters.

Shortly after the explosion of the Sultana, the steamboat Bostona (No. 2) came downriver upon the harrowing scene. The crew and passengers immediately tossed doors, shutters, stage planks, chairs, and all floating items into the water to help survivors stay afloat while rescuing approximately 150 people. Hoping to raise the alarm and get other steamboats to rush to the scene, Capt. John Watson decided to head downriver to Memphis to spread the alarm.

At Memphis, the other steamboats were already aware of the disaster. In fact, Sultana victims had begun floating past the docked steamboats at the Memphis wharf, calling out for help. While the Memphis steamboats had to wait for enough pressure to build in their cold boilers, crews sent out smaller boats and sounding yawls (a ship's smaller boats) to rescue people floating past the Memphis waterfront.

Upriver, closer to the burning Sultana, hundreds had managed to float to flooded treetops or rooftops of submerged barns or other outbuildings. As the sun began to crease, the morning darkness, the surviving soldiers, civilians, and crew awaited rescue.

Near 7:00 a.m., the still-burning hulk of the Sultana floated in among a group of flooded trees atop Hen Island, a few miles northwest of Memphis. A handful of survivors climbed back up onto the bow of the boat and fought back the flames while John Fogleman and his sons set out from Fogleman’s Landing to rescue them. Working with only a crude raft and a pole, the rescuers took the last desperate man off the boat before the Sultana sank beneath the waters of the Mississippi River.

SIDE NOTE: A LESSON IN HUMANITY

It has been said that disaster sometimes brings out the best in humanity. It is widely known that people on the Confederate side during the Civil War, even Confederate soldiers, risked their lives to save people from the deadly Mississippi River during the Sultana disaster, most of whom were Union soldiers, their common enemy just weeks earlier. In a lot of ways, this represents the beginning of healing between a divided nation, and a lesson to us all that we are all human beings.

THE AFTERMATH

In total, 786 people had to be rescued and were taken to five hospitals and the Soldiers’ Home – a sort of Civil War USO. Most of those rescued were suffering from scalds and broken bones. Almost all were suffering from exhaustion and exposure in the frigid spring water. Of approximately 50 women and children that were aboard the Sultana, only four or five women survived. Two were civilian passengers, the other crewmembers. All of the children perished.

As the dead were pulled from the river they were placed into pine coffins and set along the waterfront. Eventually, Memphis ran out of coffins and the bodies were laid next to each other on the levee, covered by blankets or cloth. Unfortunately, with the river at flood stage and running fast, most of the victims of the Sultana disaster were never recovered. Bodies were seen floating in the river days after the explosion, hundreds of miles downstream.

Only 31 of the 786 people in the hospitals or Soldier’s Home died after rescue. Three civilians were buried in Elmwood City Cemetery while the soldiers who had died in the hospitals or whose bodies were pulled from the water were buried at Fort Pickering Cemetery, just south of the city. The surviving prisoners left Memphis in three large groups, and then in twos and threes, climbing onto steamboats and going upriver to Cairo, IL, where they were transferred to a train and shipped to Camp Chase, OH. In mid-May, the men were finally released from the army and went home to their loved ones.

Capt. James Cass Mason, who took the deal from Captain Hatch to overcrowd his hobbled steamboat, lost his life in the disaster. Only 21 civilian passengers survived, out of 70, while only 28 crewmembers lived, out of the 85. Only 6 guards survived out of 22, and only 913 ex-prisoners-of-war survived out of 1,960. Of a total of 2,137 souls aboard the Sultana on April 27, 1865, there were 963 survivors and 1,169 deaths, giving the Sultana the ominous distinction of being the worst maritime disaster in American history, to this very day.

The loss of 1,047 Union soldiers (subtracting the 122 dead civilians and crew) surpasses the Union deaths on most Civil War battlefields. In fact, there were about 100 significant battles during the Civil War. If the Sultana was a battle, the number of Union deaths would put it in 11th place, compared to Union losses suffered in other battles. Only monumental battles such as Gettysburg and Shiloh had more Union deaths. Proportionately, however, if we consider deaths versus survivors, the Sultana disaster would rank number 1 with a death/survival ratio worse than any battle, for either side, during the entire Civil War.

Within days of the Sultana explosion, the U.S. government was investigating the disaster. Questions needed answers. Who was responsible for placing so many men on one boat and what had caused the explosion? Eventually, it was determined that the explosion was the result of faulty boilers, too much steam pressure, and not enough water in the boilers. The government looked into the possibility of sabotage but it was quickly dispelled. The one surviving boiler was inspected and found to contain scorching on the inside, a clear indication that the boat had been run with too little water. Also, the location of the explosion, from the top, the back-end of the boilers, far away from the fireboxes, ruled out the possibility of a coal torpedo being the cause of the explosion.

In January 1866, Captain Frederic Speed, who had been at the Parole Camp sending men out to the Sultana, was put on trial for overloading the Sultana. Captain Speed was found guilty, but after reviewing the case, the judge advocate general of the army overturned the conviction, stating that Captain Hatch was responsible for the overcrowding. Reuben Hatch, however, ignored three subpoenas and was nowhere to be found when a US Marshal was sent to arrest him and was therefore never brought to trial. Ultimately, nobody was ever held accountable or brought to justice for the 1,169 victims of the Sultana disaster.

The Sultana disaster was not the biggest news at the time, and so it never garnered the attention it deserved back then or even today. General Robert E. Lee had surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant just weeks earlier, indicating the beginning of the end of the Civil war. Abraham Lincoln had just been assassinated and his body was being transported across the United States. His assassin, John Wilkes Booth, was tracked down and killed on April 26, just one day before the disaster. Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston surrendered to Union General William T. Sherman that same date in North Carolina, and Confederate President Jefferson Davis was on the run and being pursued by Union cavalry. Too many monumental events were taking place for people and big eastern newspapers to get excited over the sinking of a steamboat or the deaths of soldiers from western states.

After disappearing beneath the waters of the Mississippi, the Sultana was eventually covered with sand and silt until she was buried deep beneath the mud on the bottom of the Mississippi River. When the river changed course and moved to the east, the buried Sultana was left under an Arkansas soybean field, approximately two miles from the river. In 1982, Memphis attorney and Sultana historian Jerry O. Potter located the buried remains of the Sultana. To this date, she still remains dormant under the Arkansas soil, a fitting memorial to the men, women, and children that were on board the Sultana between April 24 and April 27, 1865.

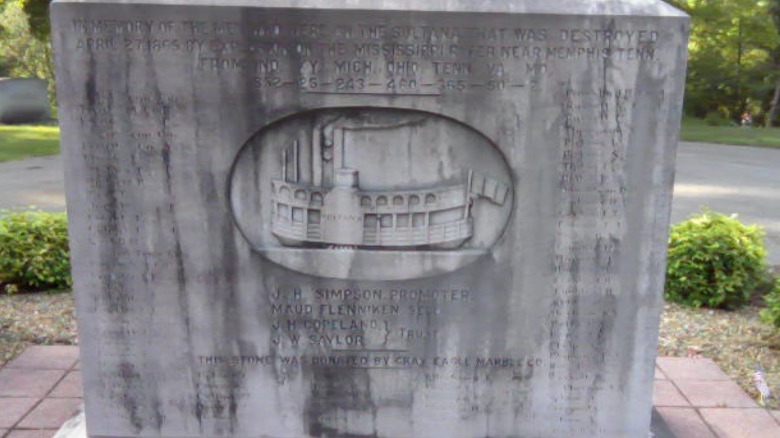

In addition to the beautiful monument erected in Mount Olive Cemetery by the Tennessee survivors in 1916, there are now monuments at the Cincinnati waterfront, where the Sultana was built, at the Vicksburg waterfront, where the Sultana was overcrowded, and at the Memphis wharf, the last place the Sultana stopped. Additionally, there are now monuments in Mansfield, OH, Franklin Township, MI, Hillsdale, MI, Delaware County, IN, Adrian, MI, Lime Creek, MI, Alliance, OH, Cuyahoga Falls, OH, and Marion, AR. Since 2015, there has been an interim Sultana Disaster Museum in Marion, Arkansas, near the last resting place of the Sultana.

- 50 Years Ago

- Point of View

- Submit an Event

- Entry Forms

- Winning Entries

This Month’s Content | Open Flipbook

Sultana Was America’s Deadliest Maritime Disaster

On April 27, 1865, the steamboat Sultana was heading upstream on the Mississippi River, carrying more than 2,000 Union Army prisoners on their way home from Confederate prisoner-of-war camps. The boat exploded at about 2 a.m. About three-fourths of the passengers burned to death, drowned or died of hypothermia — the worst death toll for a maritime accident in American history.

After Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse, the Civil War quickly drew to a close. At the time, there were thousands of POWs held on both sides. Under the terms of the surrender agreement, POWs were to be freed and sent home as soon as possible.

In the South, an estimated 5,500 prisoners at the Cahaba POW camp in Alabama and the Andersonville POW camp in Georgia were marched to Vicksburg, Mississippi. There they waited to be loaded onto boats heading north.

The first boat that took freed prisoners north from Vicksburg was the Henry Ames, which took about 1,300 men. Then a boat called the Olive Branch headed north with 700 freed prisoners.

What happened next makes no sense. The Sultana steamed into Vicksburg at about the same time as two other boats. After a couple of days, the Sultana left with more than 2,300 freed prisoners, plus an additional number of crew and passengers and a large shipment of sugar. The other two boats left Vicksburg with no freed prisoners on board but plenty of empty space.

At the time, many people raised questions about the disparity among the vessels. A former prisoner named James Brady, who was on the Sultana, said that he and his fellow troops had been “packed in more like hogs than men.” Meanwhile, the Sultana also had an official capacity of fewer than 400 people — about one-sixth its total passengers and crew!

To make matters worse, the Sultana had a leaky boiler. A Vicksburg mechanic patched it but warned ship’s captain, J. Cass Mason, that it might not hold. Mason ignored the warning.

The Sultana left Vicksburg on April 24, fighting the swollen current of the Mississippi River. The boat made stops in Helena, Arkansas, and Memphis before pulling out late on the evening of April 26.

At 2 a.m. on the 27th, the Sultana’s boilers exploded. The explosion threw many passengers and crew into the water, destroyed a large part of the boat and started a fire that quickly destroyed the rest of it.

You can read the horrible accounts of some of the survivors in books about the disaster. Some people burned to death, others drowned and many froze to death from exposure after jumping into the Mississippi River. Since few soldiers could swim at the time, most of the people who survived did so because they were able to grab parts of the floating wreckage and hold onto them until they reached shore.

No one is certain exactly how many people were killed in the Sultana explosion. Memphis attorney Jerry Potter, author of “The Sultana Tragedy: America’s Greatest Military Disaster,” estimates the number of deaths at 1,800, which exceeds by 600 the number killed when the Titanic sank in the Atlantic Ocean in 1912.

Those who did live through the experience later admitted they were very lucky. Samuel Washington Jenkins was a Union soldier from Bryson City, North Carolina, who had enlisted in the U.S. Army in Maryville. Jenkins grew up playing in some of the mountain swimming holes in the Smoky Mountains, which is why he knew how to swim. Jenkins was asleep near the boiler when the explosion blew him into the Mississippi River. Most of his fellow soldiers drowned, but Jenkins “swam as much as he could to the bank, till he could get ahold of a tree to pull himself out,” his daughter, Glenna Green, said many years later.

Jenkins eventually made it back home and eventually had 20 children, the first born in 1868 and the last in 1924. He became a doctor, practicing medicine in the Chattanooga area until his death in 1933. “He made up his mind (in the prisoner-of-war camp) that it didn’t matter what it took, he was going to work to make a doctor so that he could help humanity,” Green said.

Capt. Mason died in the accident. Frederick Speed, a U.S Army officer, was found guilty of grossly overcrowding the Sultana. His verdict was overturned by the Army, so the U.S. government never punished anyone for the disaster.

About 195 of the soldiers killed in the Sultana explosion were East Tennessee residents who fought for the Union cause. That’s why there’s a Sultana monument at the Mt. Olive Baptist Church Cemetery in Knoxville.

Bill Carey founded Tennessee History for Kids in 2004. The non-profit organization helps teachers cover Tennessee history, American history, civics and basic social studies, and uses booklets, posters, inservices and the website www.tnhistoryforkids.org. Carey was a reporter in Nashville through most of the 1990s and has written six books, among them Fortunes Fiddles and Fried Chicken: A Nashville Business History and Runaways, Coffles and Fancy Girls: A History of Slavery in Tennessee.

Related Posts

Shutterbug showcase – 95 reasons to celebrate tennessee, the coolest thing made in tennessee, the original ‘tennessee titan’.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Type above and press Enter to search. Press Esc to cancel.

This Civil War Boat Explosion Killed More People Than the ‘Titanic’

The ‘Sultana’ was only legally allowed to carry 376 people. When its boilers exploded, it was carrying 2,300

Kat Eschner

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/28/32/28328031-3d8f-4c3c-aae1-32e4627e8bde/steamboat.jpg)

The Civil War was the deadliest conflict in U.S. history. But one of its lesser-known gory episodes actually happened after the war ended, as Union prisoners of war made their ways home—or tried to.

On this day in 1865, a steamboat carrying 2,300 recently released Union POWs, crew and civilians sank after several of its steam boilers exploded. An estimated 1,800 people died, of causes ranging from steam burns to drowning, making the explosion of the Sultana the deadliest maritime disaster in U.S. history— worse than the Titanic . Although the disaster got little press in its own time and remains little-known today, the city of Marion, Arkansas has ensured it is not forgotten.

For a nation saturated by news of war and death, writes Stephen Ambrose for National Geographic , one more catastrophe just wasn’t that newsworthy. “April 1865 was a busy month,” Ambrose writes. Confederate troops under Robert E. Lee and Joseph Johnson surrendered. Abraham Lincoln was assassinated and his assassin caught and killed. Confederate President Jefferson Davis was captured, ending the Civil War.

The public’s news fatigue was at a high, and the death of fewer than 2,000 people—stacked up against the roughly 620,000 soldiers who died during the Civil War, to say nothing of civilians—didn’t register on a national scale, Ambrose writes. The disaster was relegated to the back pages of Northern newspapers.

For the survivors of the Sultana and the communities on the banks of the Mississippi near the explosion, though, the disaster was hard to miss, writes Jon Hamilton for NPR. The rescue effort that followed the disaster “included Confederate soldiers saving Union soldiers they might have shot just weeks earlier,” he writes.

“Many Sultana survivors ended up on the Arkansas side of the river, which was under Confederate control during the war. And many of them were saved by local residents,” Hamilton writes. Those residents included John Fogleman, “an ancestor of the city of Marion's current mayor, Frank Fogleman .”

The 1865 Foglemans were able to rescue about 25 soldiers and sheltered them, Hamilton writes. Newspaper accounts from the period also point to a Confederate soldier named Franklin Hardin Barton, who had been involved in the river patrol, saving several of the soldiers he would have been obliged to fight on the river just a few weeks earlier. And those aren't the only examples.

Like most Civil War events, the explosion of the Sultana has attracted its share of historical sleuths. Many place the blame for the horrific disaster on a profit-minded captain who didn’t care if pesky regulations got in the way, writes Hamilton. The steamboat was only registered to carry 376 people, writes Ambrose. It was carrying more than six times that number.

One Sultana researcher told Hamilton that it’s clear J. Cass Mason “had bribed an officer at Vicksburg to ensure that he would get a large load of prisoners.” According to Jerry Potter, the damaged boiler had already received a half-hearted repair. The mechanic who did the work “told the captain and the chief engineer the boiler was not safe, but the engineer said he would have a complete repair job done when the boat made it to St. Louis," Potter says.

But the boat didn’t make it, and locals are still haunted by the tragedy. For the 150th anniversary of the disaster in 2015, the city of Marion, Arkansas created a museum that shows how the Sultana explosions happened and memorializes those aboard.

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

Kat Eschner | | READ MORE

Kat Eschner is a freelance science and culture journalist based in Toronto.

Remembering the Sultana Explosion

M ost Americans likely associate maritime tragedies with ocean liner disasters such as the Titanic and the Lusitania , or with violent storms like those documented in The Perfect Storm and The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald . But the worst maritime disaster in American history, and the fourth deadliest ever recorded, was the explosion on board the steamboat Sultana on April 27, 1865, when approximately 1800 people, the vast majority recently freed Union Army prisoners of war, lost their lives on the Mississippi River near Memphis.

Before the proliferation of railroads, the easiest and fastest way to transport goods and people was over water. Shallow waters remained problematic obstacles into the early nineteenth century, but technological advances, chief among them vessels equipped with boiler-produced steam propulsion, allowed both for further navigation of shallows and for upriver navigation against strong currents. Rapid additional exploitation of the nation’s waterways ensued, catalyzing the westward expansion and economic development of the United States.

Although steam power was an exciting technology that appeared to offer limitless possibilities, boiler construction, manufacture, maintenance, and operation were hardly perfected when steamboats began appearing in American waters. Combined with a lack of government or industry oversight, inspection, or regulation, such mechanical uncertainty meant that steamboat fires and boiler explosions were common occurrences. Historian John Burke has estimated that 233 boiler explosions occurred on steamboats between 1816 and 1848. Between 1825 and 1830, forty-two explosions killed 273 people in the United States, and between 1810 and 1840, nearly 4000 fatalities occurred on the Mississippi River alone.

The deaths of more than 300 people from steamboat boiler explosions in the spring of 1838 finally spurred Congress to issue the first national public safety regulatory act. But even though the Steamboat Act of 1838 required ships to be registered, provide safety equipment, and undergo periodic inspection, steamboat boilers continued to explode at an alarming rate. Between 1841 and 1848, seventy more boiler explosions caused 625 deaths, and in just the eight months prior to the passage of the next national safety legislation in 1852, 700 people died in boiler accidents. The Steamboat Act of 1852 finally set standards for boiler construction and operation, including the hydrostatic testing of boilers and provision of steam safety valves, as well as licensing requirements for steamboat pilots and engineers. These provisions made things somewhat safer, and yet steamboats still caught fire and blew up with some frequency, leaving travelers feeling vulnerable and powerless in the face of such fickle machines.

Historian Walter Johnson has claimed that boiler explosions “were the nineteenth century’s first confrontation with industrial mayhem.” While most mourned and winced at the mechanized chaos, others eagerly exploited people’s fascination with death and destruction. A disaster porn print industry arose to titillate Americans and morbidly monetize the grim tragedies. Lloyd’s Steamboat Directory, and Disasters on the Western Waters , filled with gruesome and graphic descriptions of human physical suffering and death, including a showcase of 32 woodcuts, was one of the best-selling books of the 1850s.

Part of the fascination with such horror was the fact that these terrible accidents cut across lines of class, race, sex, and geography. Between 1831 and 1838 three Congressmen and a Senator died in steamboat explosions on the Red River, the Ohio River, and the Atlantic Ocean. A boiler explosion aboard the Hudson River steamer Henry Clay in 1852 claimed the lives of Stephen Allen, the former mayor of New York City, and of Andrew Jackson Downing, the father of American landscape architecture and park planning. Transatlantic academic fugitive revolutionary Karl/Charles Follen, who introduced German language study, Christmas trees, and gymnastics into American society before being dismissed from Harvard for his radical abolitionist activities, died in 1840 in a fire aboard the New York-Boston steamer Lexington . Mark Twain’s brother, Henry Clemens, died from injuries sustained from a boiler explosion on the Mississippi River steamer Pennsylvania in 1858.

With hindsight, it seems strange that a major military-related steamboat explosion had not occurred until the Sultana tragedy. The end of the Civil War presented many new challenges to the victorious Union, among them a daunting number of nightmarish logistical tasks necessary for returning the country back to normal. One of the first was repatriating tens of thousands of Union soldiers from southern battlefields, encampments, and prisons back to their homes and families in the North, where they could be formally demobilized, discharged, and — with luck — reintegrated into civilian society. The Mississippi River, the country’s major north-south transportation artery and with connections to almost the entire nation by via its massive river basin, was naturally viewed as the best avenue for troop transport and dispersal.

In the months after Appomattox, Union soldiers in the Deep South made their ways by foot, horse, train, and boat from their southern postings, and from notorious prisons such as Andersonville and Cahaba from which they had been paroled, towards Mississippi River ports such as New Orleans, Memphis, and Vicksburg, in the hopes of being able to board a northbound ship. The American government lacked the marine resources to execute the return of tens of thousands of men, and so it turned to the private sector for assistance, paying independent steamship operators as much $10 for each soldier they transported back north. The operators of the Sultana hoped to capitalize on such an opportunity.

The Sultana was a private Mississippi River side-wheel steamboat with a maximum capacity of 375, and was captained by J. Cass Mason as it headed south from St. Louis in mid-April 1865. By the time it reached the Union army outpost at Vicksburg, it already had 180 people onboard, but the profits to be realized by both the owners of the Sultana and by army officials, who received kickbacks for providing “passengers,” were too great to pass up. In Vicksburg, approximately 2200 more persons were packed onto the ship.

When the Sultana docked in Vicksburg, one of its boilers had already begun leaking dangerously. A proper repair would have taken several days, but Captain Mason, afraid of losing his lucrative cargo of soldiers to other steamboat competitors, ordered the precariously leaking boiler simply to be patched. On April 24, the overcrowded vessel left Vicksburg, headed upriver for Cairo, Illinois. Carrying more than six times its design capacity, the ship struggled mightily upstream against the Mississippi’s famously strong currents, which had been exacerbated by a heavy spring snowmelt. On April 27, the Sultana had gotten just north of Memphis when the patched boiler exploded. The resulting fire caused the ship’s other boilers to explode, and approximately 1800 passengers died from the explosions, fire, hypothermia, or drowning.

Nearly the same number of American troops perished in the Sultana disaster as did in the entire Spanish-American War, the War of 1812, or the current ongoing war in Afghanistan. The disaster has been the subject of stories by NPR, Smithsonian magazine, and National Geographic , not to mention countless academic articles. PBS’s History Detectives dedicated an episode to debunking the rumors of potential Confederate sabotage via a bomb disguised as a piece of coal. The Sultana Disaster Museum is located in Marion, Arkansas, and reunions of the descendants of survivors continue to occur.

Yet the wreck of the Sultana remains unfamiliar to the general public, an elision that has several probable causes. April 1865 was filled with “exciting” events – the end of the Civil War, the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, the capture and death of John Wilkes Booth. The Sultana accident did not have the luxury of occurring in a relatively slow month for news, like the Titanic sinking did nearly 47 years later. Moreover, unlike the Titanic or the Edmund Fitzgerald , the Sultana itself had little beyond the death toll to draw the public’s fascination. The vessel was neither state of the art nor did it carry famous people. The Union troops onboard were only enlisted men, chiefly recent parolees from Confederate prison camps. Additionally, Americans were tired of war and wanted to move past it rather than deal with yet another tragedy. Moreover, the years of war had deadened people to loss. The Sultana was seen just another event of suffering and loss, with a death total akin to a minor Civil War battle. Unless there was a specific personal connection to a victim, there was just detached numbness.

But another theory for the rapid disappearance of the Sultana from American historical memory might, ironically, be related to the fact that the Sultana was an utterly preventable tragedy, grounded in greed, bribery, war profiteering, and obvious criminal negligence. Everybody thinks their lives and personal safety are worth more than $10. Few want to imagine that they could ever be put in such a hapless situation, where their destinies are subject to the whims of profit-seeking operators of an often hazardous industry where corners routinely get cut for financial gain. No one wants to confront their utter powerlessness amidst the chaos of a scorched postwar environment and a seemingly unsympathetic world.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Policy

- American History

21 Images Depicting the Sultana Disaster of 1865

In late April, 1865, the Civil War was coming to an end. Union and Confederates decided that the POWs should be released. Prisoners Cahaba, Andersonville, and Libby Prisons were sent to the Vickersburg, Mississippi to take steamboats up the river into the North and home to their families.

The steamboat companies competed amongst each other to take the most freed prisoners up river. Each company was paid $5 ($90) per enlisted men and $10 ($180) per officer transported. The Sultana was one of the steamboats carrying soldiers up river. She was designed to carry about 375 passengers and crew members.

On April 24, 1865, The Sultana was loaded with 1,978 paroled prisoners, 22 guards from the 58th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, 70 paying cabin passengers, and 85 crew members.

The Sultana traveled up river for two days, fighting one of the worst spring floods in the Mississippi’s history. In some places the river was three miles wide.

Around 2:00 a.m. on April 27, 1865, just seven miles north of Memphis, The Sultana’s boilers exploded destroying major sections of the boat, and igniting a large fire. The weak freed prisoners who survived the explosion were forced to attempt to swim through the cold, fast moving waters.

Approximately 1,700 people died. The Sultana disaster was the worst maritime disaster in American history, causing more deaths than the sinking of the Titanic.

The Sultana disaster remains a relatively unknown tragedy because it was over shadowed by Abraham Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, and John Wilkes Booth, Lincoln’s assassin, was killed April 26, just one day before the Sultana tragedy.

NEXT >>

<< Previous

HSB Equipment Connection Blog

What happened to the sultana: the greatest maritime disaster in us history, what happened.

In the early morning hours of April 27th 1865 the steamboat Sultana was seven miles north of Memphis, Tennessee, when three of the four boilers exploded . The explosion and resulting fire remain the largest maritime disaster in U.S. History . Over 1,700 lives were taken by the explosion, the fire, and the cold Mississippi river waters.

The majority of the passengers on the boat were soldiers who had recently been released from Confederate prisoner of war camps . These men had survived horrendous conditions, most were starved, and all were looking forward to returning home to their families and farms. They considered themselves lucky, as many of their friends did not survive the war.

The boilers on the Sultana were less than three years old, but they were in horrible condition. The iron plates were burnt, one of the boilers had two repairs in two months and they had already been re-tubed once. Although the inspection 15 days before the explosion indicated they were safe, they were not.

The fatal four that caused the tragedy

1. material of construction.

The iron (Charcoal Hammered No. 1) used in construction was a poor quality iron. While it was the best available material of the day, it was not a suitable boiler material. This type of iron gets brittle when it is overheated and cooled repeatedly. By the late 1800’s, the textbooks noted that CH No. 1 iron was “not a suitable iron for boiler construction.”

2. Water Treatment

These boilers had no water treatment and used water straight from the Mississippi River. The mud in the water settled on the plates and surfaces acting as an insulator between the water and the iron. This caused the iron to repeatedly overheat and burn. As noted, this iron gets brittle when it is overheated and cooled repeatedly.

3. Boiler Design

The Sultana boilers were a firetube design. They used 24 smaller flues instead of the traditional two larger flue design. This larger number of smaller tubes arranged closely together made the boilers hard to clean exacerbating the Mississippi River mud settling on the boiler bottom. This design proved to be incompatible with the material of construction and the water quality and these boiler designs were removed from the Mississippi river.

These points are supported by testimony while accounting for what engineers did not know about explosions at the time. They match the statistics of boiler explosions of the time and the science of boiler explosion theory. These boilers were almost destined to explode and unfortunately, the boat was packed with those doomed passengers when they finally did.

4. Greed and corruption

It was later determined that 2,400 people were stuffed onto the Sultana when legally it could only carry 376. What’s even more astounding is that two boats left the wharfs empty that same day. Greed and corruption are the reason for this. Numerous books have been written on the subject and a documentary, “ Remember The Sultana ” premiered on the 150th anniversary of the tragedy. HSB’s Patrick Jennings was asked to shed light on the boiler explosion in the film. You can find the documentary on Amazon Prime starring Lord of the Rings’ actor Sean Astin.

HSB is born

It was two members of the Polytechnic Club, a Hartford, Connecticut based organization consisting of businessmen who gathered “to discuss matters of science in relation to everyday life,” that took action in the aftermath of the Sultana.

Jeremiah Allen and Edward Reed formed a boiler insurance company that tied boiler inspections and insurance together as a package. Allen and Reed founded The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company (HSB), which was incorporated in June of 1866 in Hartford, Connecticut, still the company’s home today.

Other modern day benefits stemming from this disaster include the inspection and insurance industry as well as codes such as the ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code and the National Board Inspection Code.

Want more information like this delivered straight to your inbox? Click the “Follow” button on the bottom of the screen and enter your email address.

© 2021 The Hartford Steam Boiler Inspection and Insurance Company. All rights reserved. This article is for informational purposes only and is not intended to convey or constitute legal advice. HSB makes no warranties or representations as to the accuracy or completeness of the content herein. Under no circumstances shall HSB or any party involved in creating or delivering this article be liable to you for any loss or damage that results from the use of the information contained herein. Except as otherwise expressly permitted by HSB in writing, no portion of this article may be reproduced, copied, or distributed in any way. This article does not modify or invalidate any of the provisions, exclusions, terms or conditions of the applicable policy and endorsements. For specific terms and conditions, please refer to the applicable endorsement form.

Share this:

Leave a reply cancel reply.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Necessary These cookies are not optional. They are needed for the website to function.

- Statistics In order for us to improve the website's functionality and structure, based on how the website is used.

- Experience In order for our website to perform as well as possible during your visit. If you refuse these cookies, some functionality will disappear from the website.

- Marketing By sharing your interests and behavior as you visit our site, you increase the chance of seeing personalized content and offers.

Discover more from HSB Equipment Connection Blog

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- September 9, 2024: Your Chance to Preview The Killer’s Game

Animated Map of the 2022 Russian Invasion of Ukraine (through August 27th, 2024)

- A Timeline of European History Since 1648

- A Timeline of European History to 1648

- In Space, the Audience Can Hear You Scream! (Movie Review)

- History Short: Dreams are Made of Treasure!

- History Short: The First Country with Equal Rights for Women

- History Short: Toughest Human Alive!

April 27, 1865: Riverboat SS Sultana Sinks in Mississippi, or the Worst US Maritime Disaster of All Time

A Brief History

On April 27, 1865, the paddle-wheel steamboat, SS Sultana was carrying 2427 people when she blew up, killing 1800!

Digging Deeper

The Mississippi steamboat was jammed with soldiers returning North from the Civil War , mostly Union soldiers who had been in Confederate prisoner of war camps (especially Cahawba and Andersonville).

Crowded onto the riverboat designed to carry only 376 people, many of the soldiers were emaciated and ailing from their time in the horrendous prison camps. The ship had started from New Orleans and had made a stop at Vicksburg (Mississippi) in order to repair a boiler. The repair was hastily done in a slip shod manner to avoid the 3 day delay that replacing the boiler would entail. Fate determined that choice was a grave mistake.

Struggling under the extreme overload against the strong Mississippi River spring current, the engineers probably overloaded the pressure in the boilers in order to continue to make good speed. After the ship had passed Memphis 7 or so miles ago, at 2 a.m. a huge explosion tore the ship apart and sent passengers flying! Obviously, a boiler had exploded, the greatest fear of riverboat sailors in those days.

Not only was the ship grievously damaged, but it was also now a burning hulk. Drifting to the west bank, the burning hulk sank around dawn. Passengers not killed in the initial explosion or injured when hurled into the water and drowned had a choice: stay with the ship and burn, or jump into the freezing cold water. Neither choice was desirable, as the cold water quickly sapped the strength of the people trying to swim and the powerful current took them downriver.

Several steamboats rushed to the rescue and picked up as many survivors as possible, with about 500 burned and injured survivors taken to hospitals in Memphis. Of those, at least 300 ended up dying anyway. Hypothermic swimmers could resist the cold no longer and drowned by the scores.